Previous Issues

Summer 2024. Issue 409

Suite de Pièces pour Violon et Orgue

Spring 2024. 408

Winter 2024. 407

Autumn 2023. 406

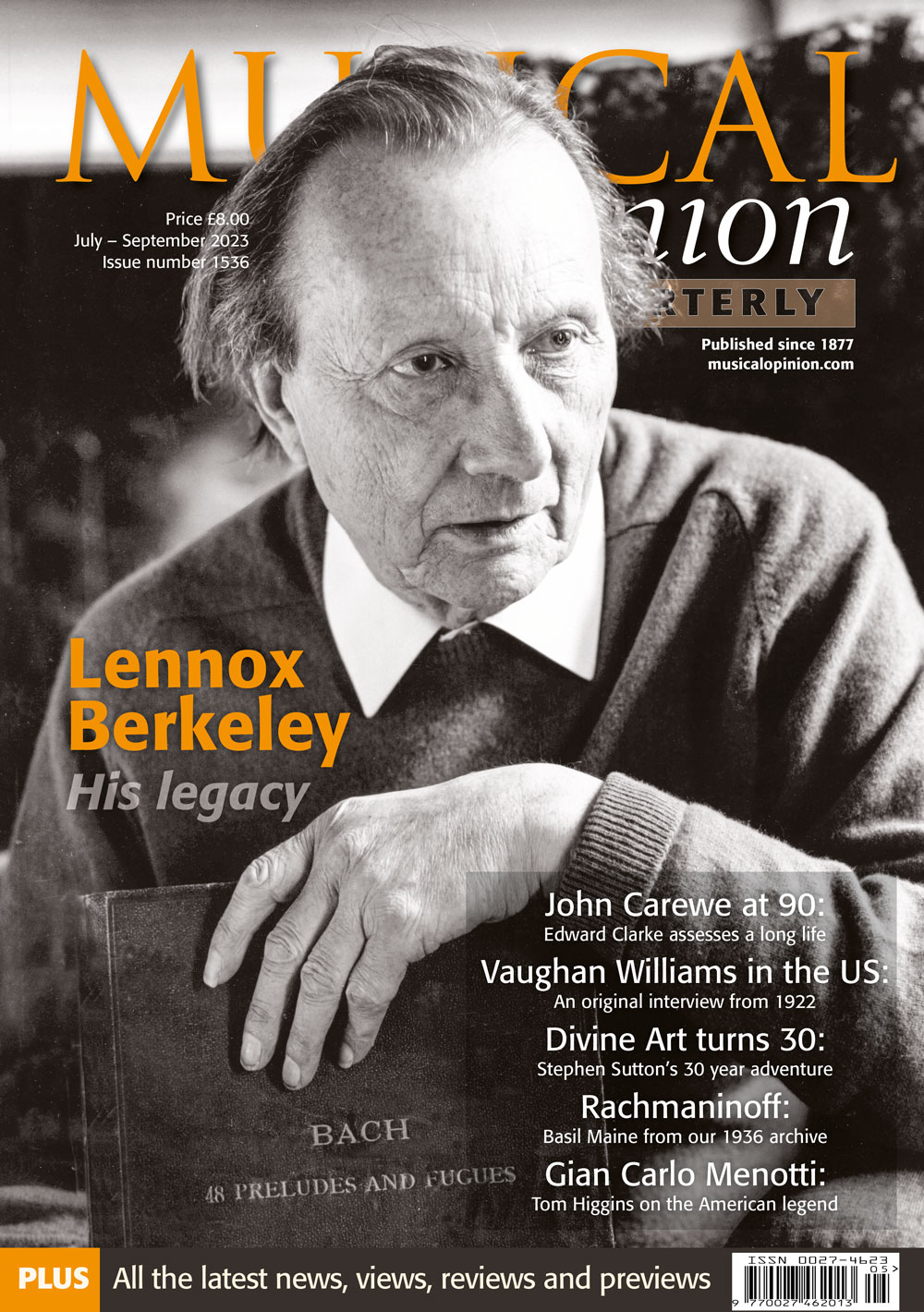

Summer 2023. 405

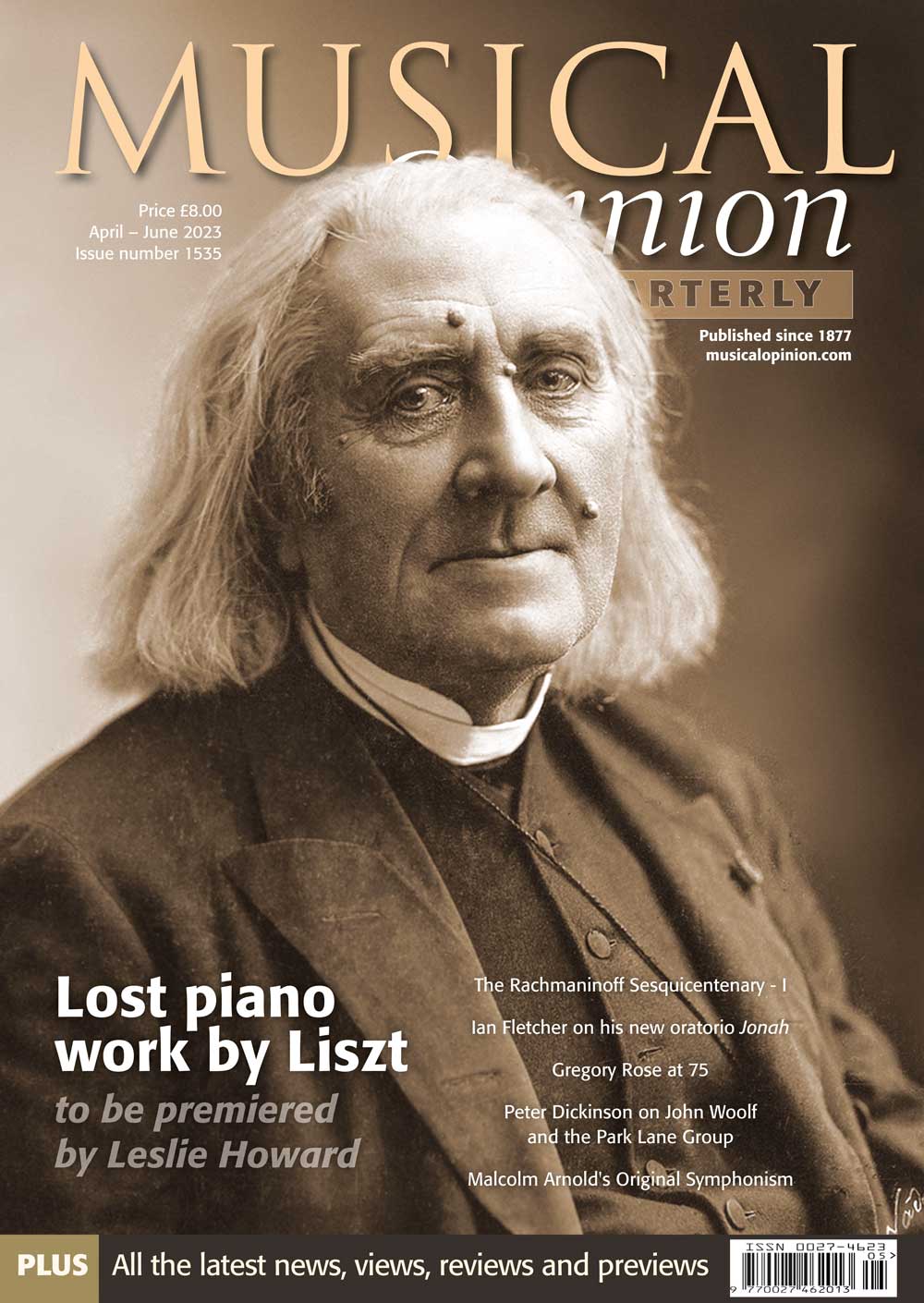

Spring 2023. 404

Winter 2023. 403

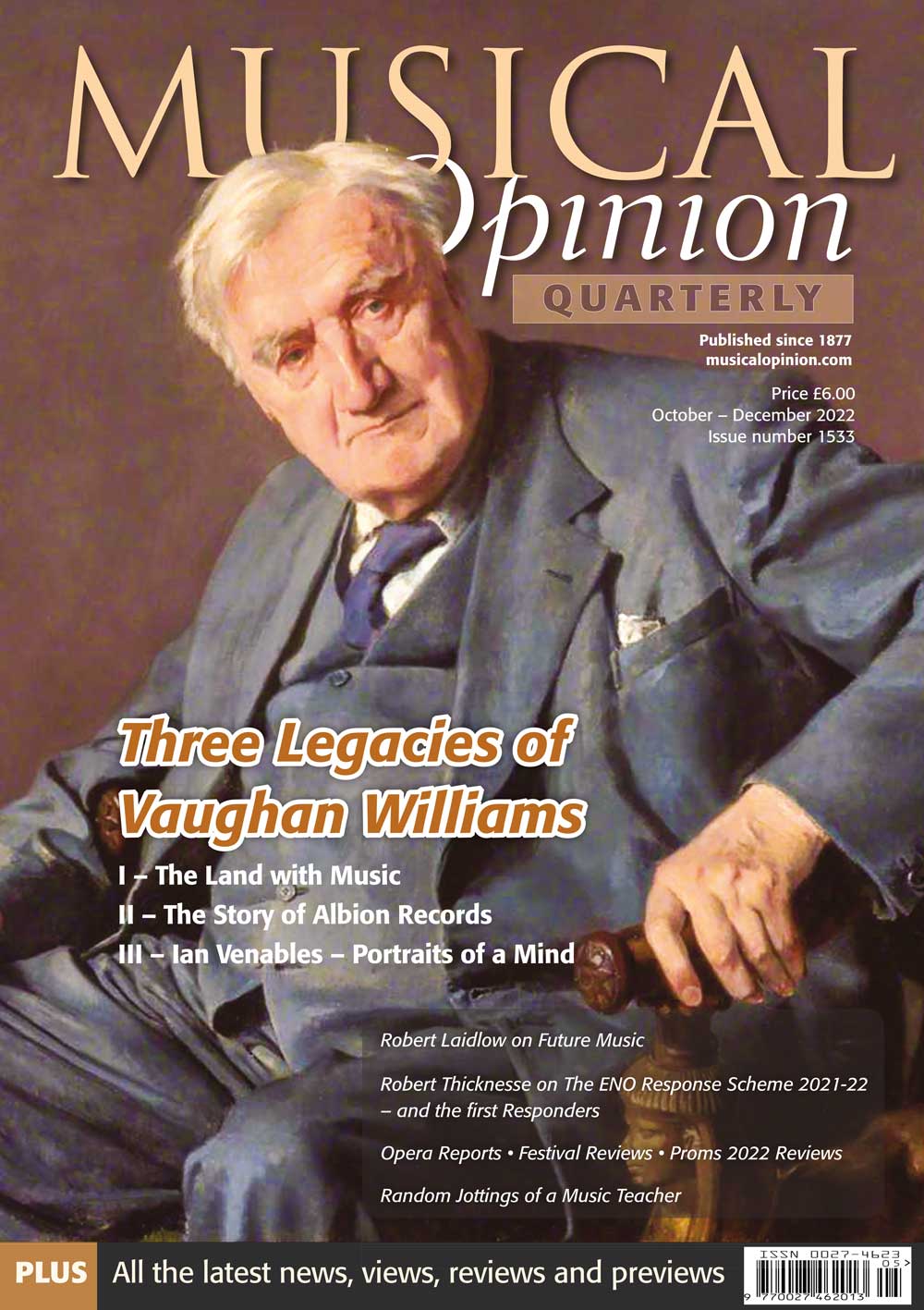

Autumn 2022. 402

Summer 2022. 401

Spring 2021. 400

Winter 2021. 399

Autumn 2021. 398

Whilst staying at A4 size and 56 pages, the magazine has been completely redesigned with different fonts (more easy to read), bigger photopgraphs, more focus on things like specifications and more CD reviews of organ repertoire.

Summer 2021. 397

Winter 2021. 395

Spring 2021. 396

Autumn 2020. 394

Spring 2020. 392

Winter 2019. 390

Autumn 2019. 389

Explore By Topic

Summer 2020. 393

The Organ of St Alban’s Cathedral

Tom Winpenny

The Benedictine monastery of St Alban, founded about 739, was built on the site of the execution of Britain’s first martyr, St Alban (d. c. 250AD). Various small organs are recorded as having existed in the Abbey Church before the dissolution of the monastery in 1539, but after that there is no record of an organ in the building until 1820, three centuries after the townspeople of St Albans had bought the Abbey as their Parish Church. In 1861 a three-manual organ by William Hill was installed: in 1885 it was enlarged and remodelled by Abbott & Smith of Leeds during the restoration of the building, which coincided with its elevation (in 1877) to Cathedral status. Further work was undertaken in subsequent decades to improve the projection of sound throughout the 521-foot-long building: new organ, designed by John Oldrid Scott, were installed in 1908 and in 1929 the organ was re-voiced by Henry Willis to be much louder.

In 1958 Peter Hurford was appointed as the Cathedral organist: he was quickly gaining an international reputation as a brilliant performer and his appointment coincided with further restoration work to the Cathedral fabric, which necessitated the dismantling of the mechanically unreliable and tonally inadequate organ. Working closely with an adviser, Ralph Downes, Hurford drew up a specification for a new instrument inspired by the latest trends in organ building from Europe; it would accompany services – in particular, the core English cathedral repertoire – in both the nave and quire, and would also serve well for most of the solo repertoire. It would become the first English cathedral instrument to be built on Neo-Classical principles. The contract was placed with organ-builders Harrison & Harrison of Durham; assembly in the Cathedral began at Easter 1962 and the organ was dedicated in November of that year. WITH FULL SPECIFICATION

The perception of organ music

Dr Michal Szostak

The distinguished author discusses the analysis and detailed understanding of the artwork process by the creator (performer, improviser, composer) and receiver.

My considerations in terms of the aesthetics of organ music have been concerned mainly from the perspective of the musician, who – when being fluent in his field of art – can be called an artist. In this article I will focus on the second but no less important subject of the aesthetic situation, the recipient. It is the recipient who is the addressee of a work of art created during the creative process and received in the perception process. It is in the process of perception – receiving, learning about the work, experiencing its value, understanding it, accepting or rejecting it – that the aesthetic object and personality of the recipient are shaped.

Organ music and its lictenerss constitute a unique category of music. In an organ recital, this uniqueness will be slightly smaller; however, if we mean liturgical organ music per se, then the perception of this music takes on new contexts, becoming unique and requiring special, separate analysis. Using a certain metaphor, there are three “universities” of music performance where a musician will learn how to play well: a church, a pub and a circus. .

The organ music of Vincent Persichetti

Andrea Olmstead

Few twentieth-century American composers have been more universally admired than the warm, funny and much-loved Vincent Persichetti (1915–1987).

His contributions have enriched the entire musical literature, and his influence as performer and teacher is immeasurable. While on the composition faculty at the Philadelphia Con servatory, from 1939 until 1962, he began his forty-year career at The Juilliard School (1947–87), where he taught Philip Glass and Steve Reich, among many other composers. A concert pianist and skilledconductor, he wrote Twentieth-Century Harmony, a popular textbook that has never been out of print.

At six, Persichetti started a decadelong study of the piano with Warren Elberson Stanger, followed by lessonswith the founder of the nearby Combs Conservatory in Philadelphia (Persichetti’s home town), Gilbert Combs, who was also an organist. After study with Alberto Jonás, Persichetti landed with his last piano teacher, Olga Samaroff Stokowski (the first of Leopold Stokowski’s three wives), at the Philadelphia Conservatory. His principal composition teacher, Russell King Miller, was also active as an organist.

Jennifer Bate (1944-2020) – a memoir

Peter Dickinson

Jennifer Bate had an outstanding international career as a concert organist. She came from a family of organists and the role of her father was crucial. As she relates, her travels were astonishing. There were months when she hardly appeared in the UK because she was on tour. Figures speak for themselves: she played in over forty countries; gave some 90 recitals in France and at least 150 in Italy; she toured South America eleven times; and appeared at major international festivals including Salzburg, Echternach, Heilbron, Vienna, Tokyo, Auckland, Reykjavik, Bergen, St Petersburg, Graz, Lockenhaus and Stavangar. Her schedule was astounding. Some of her difficulties she describes were the result of being a woman on her own especially in those days. Bate’s determination to survive every kind of problem – and danger – was simply amazing: she triumphed over obstacles that would have defeated most people. Her connection with Messiaen was a major feature of her life from 1975 until his death in 1992. His desire to have her record all his organ music again on his own instrument at La Trinité shows that he had more confidence in her than in any other performer British or French, but he died before it could be done. Bate’s memories of her connections with Messiaen are of absorbing fascination.

Keble College, Oxford, at 150

'The Blue Riband' of organ scholarships

While many of the events planned to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Keble College, Oxford, have been put on hold due to the Covid-19 pandemic, here former College Fellow, Kenneth Shenton, takes a timely look back at some of its most illustrious early organ scholars. At the same time he also takes the opportunity to record the quite unique and longstanding contribution made both to the college and to the organ world by its distinguished former Sub Warden, Dr George Parkes.

Opening its doors exactly 150 years ago in 1870, Keble College, Oxford, remains a superb monument to high Victorian confidence as expressed by its architect, that high priest of modern gothic, William Butterfield. Named in honour of the leader of the Tractarian Movement, John Keble, who had died four years earlier, this all male institution was founded in his memory. Though its history may be short in terms of other Oxford colleges, nevertheless the musicians it produced, particularly during the first half of the last century, exerted an ever increasing influence on the world of music. Perhaps none more so than the holders of what the former Prime Minister, Edward Heath, in his celebrated book, Music A Joy For Life, once famously dubbed as, The Blue Riband of Organ Scholarships.