Previous Issues

Summer 2024. Issue 409

Suite de Pièces pour Violon et Orgue

Spring 2024. 408

Winter 2024. 407

Autumn 2023. 406

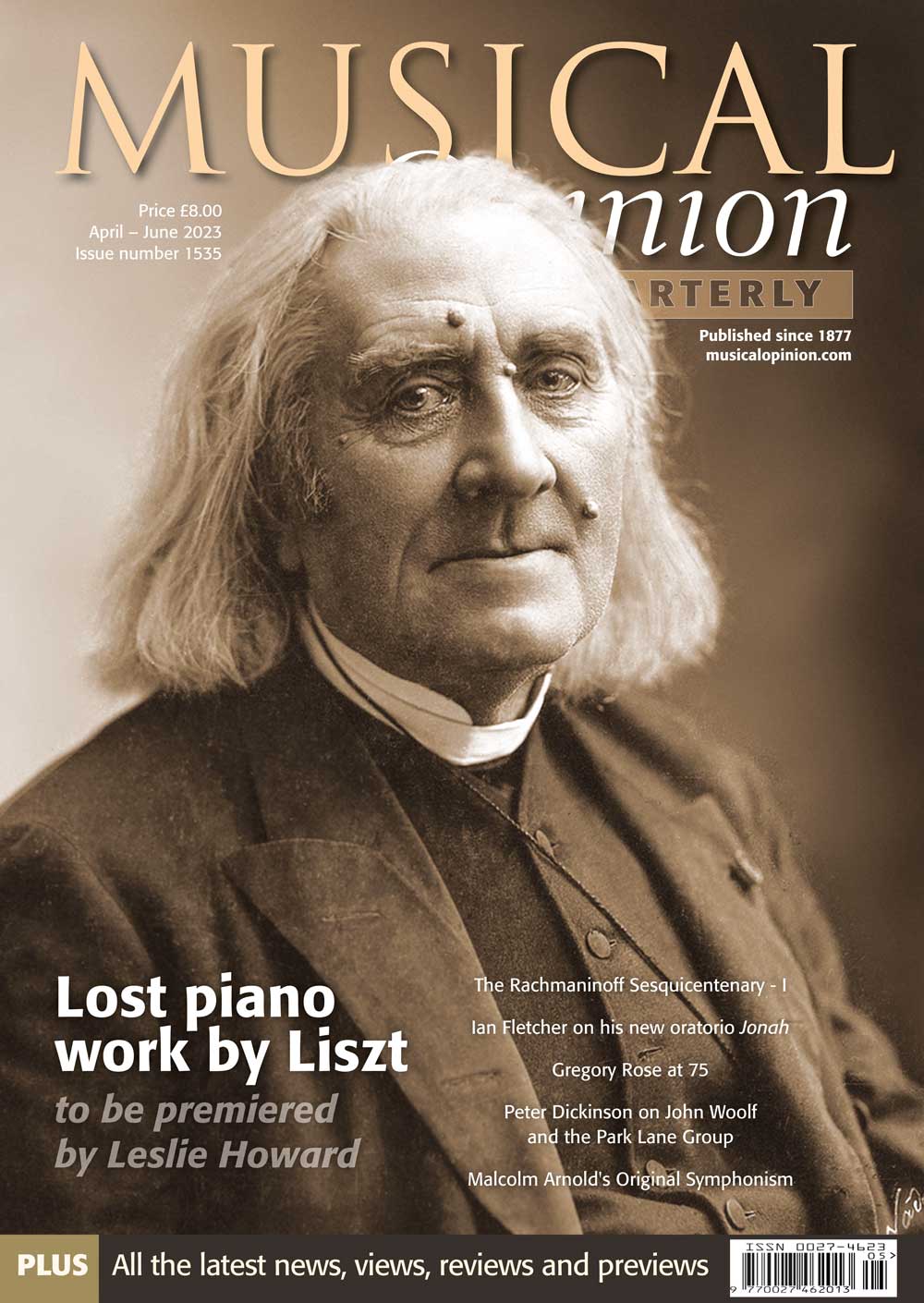

Spring 2023. 404

Winter 2023. 403

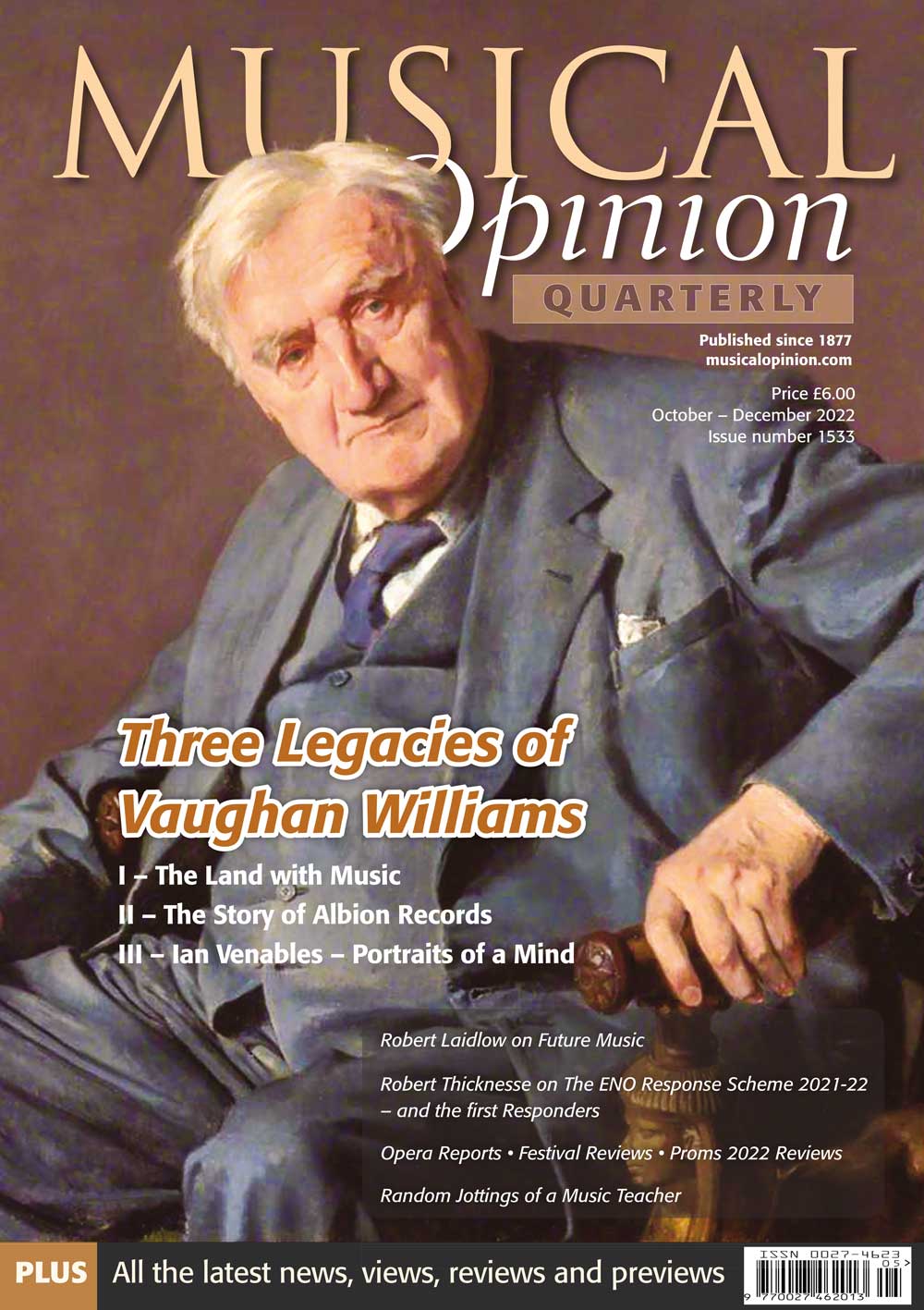

Autumn 2022. 402

Summer 2022. 401

Spring 2021. 400

Winter 2021. 399

Autumn 2021. 398

Whilst staying at A4 size and 56 pages, the magazine has been completely redesigned with different fonts (more easy to read), bigger photopgraphs, more focus on things like specifications and more CD reviews of organ repertoire.

Summer 2021. 397

Winter 2021. 395

Spring 2021. 396

Autumn 2020. 394

Summer 2020. 393

Spring 2020. 392

Winter 2019. 390

Autumn 2019. 389

Explore By Topic

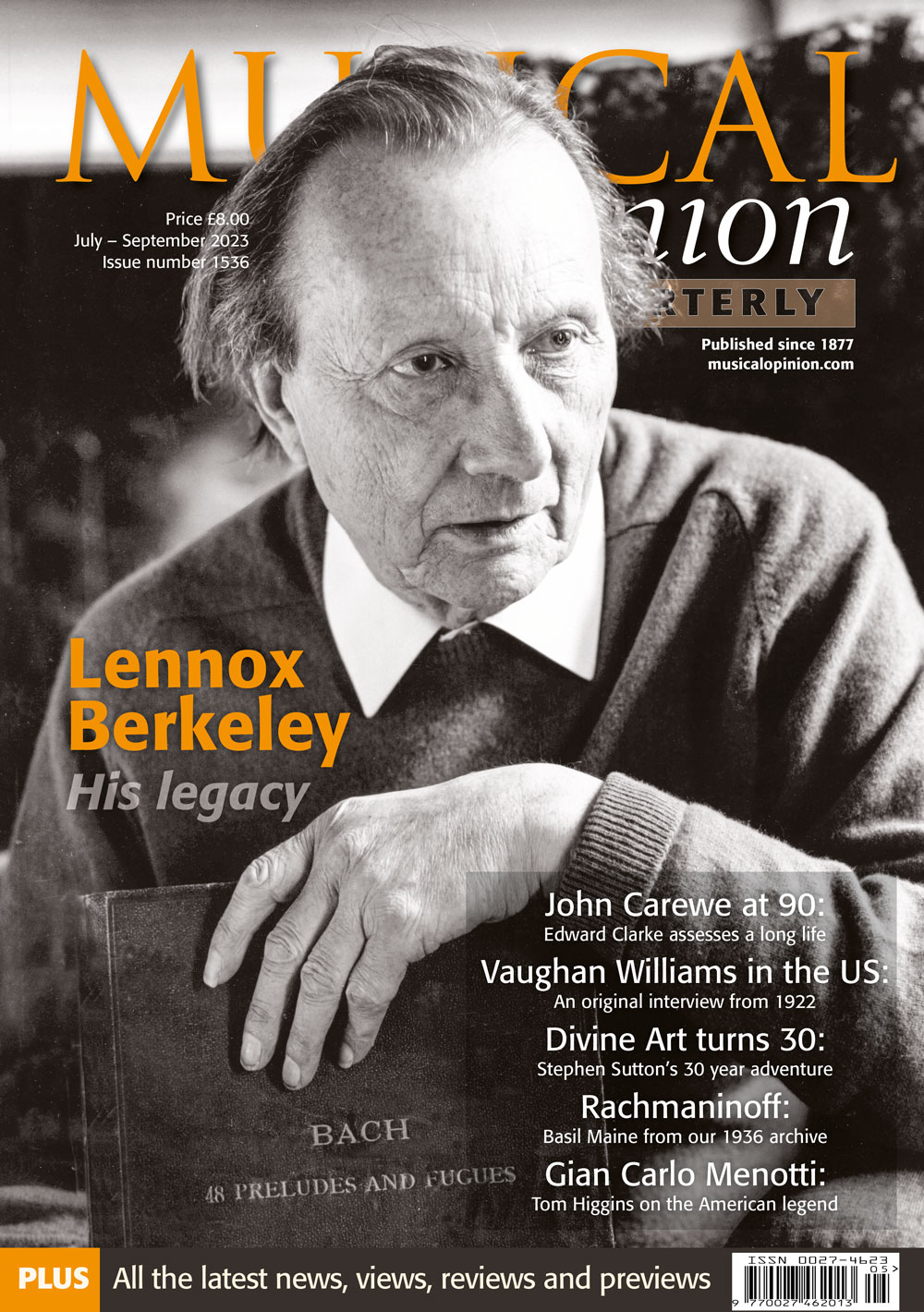

Summer 2023. 405

The Essentials of Organ Improvisation

Dr Michal Szostak

Organ improvisation is a practical, noble, respectable art with an intense history and remarkable achievements. Although the results of practising it are ephemeral, the theoretical descriptions and volumes written about it allow us to conclude that it is an essential phenomenon for humanity in music. Depending on the adopted optics, a look at organ improvisation will be characterised by issues and cognitive apparatus characteristic of a given discipline.

Following and developing concepts presented in my article, ‘The Art of Stylish Organ Improvisation’ published in issue 390 of “The Organ” (Szostak, 2019) and my paper, ‘Creativity and Artistry in Organ Music’ from issue 391 (Szostak, 2020), in this current study I should like to look at the phenomenon in an interdisciplinary manner, from three seemingly distant perspectives: 1) instrumental studies – as the primary field, on which, from the practical side, every musical improvisation takes place; 2) aesthetics – as a theoretical science on art and beauty derived from philosophy, and 3) management – as a field both theoretical and practical, combining the components of science (knowledge) and art (skills), and dealing with the efficient implementation of goals.

This article aims to answer the following research questions: first, How can aesthetic theory broaden our view of the improvisation process? And second, What is the difference between virtuosity, artistry and creativity in improvisational activities? The following research methods were applied to answer these questions: a critical analysis of the literature in the field of instrumental music, aesthetics and management, as well as the autoethnography of an organist with over 20 years of experience, a university professor and researcher in the field of management aesthetics, creation and creativity.

WITH MANY PHOTOGRAPHS AND SPECIFICATIONS

Howard Blake: The Rise of the House of Usher Opus 532 (2003)

Robert Matthew-Walker

The music of Howard Blake is known world-wide, essentially through his haunting song ‘Walking in the Air’, a truly inspired theme that has become one of the most significant pieces of music to be heard at Christmas-time. Many composers would have been satisfied to have settled with that song, to sit back and luxuriate in the fruits of the income such a haunting theme has wrought.

But for Howard Blake, who celebrates his 85th birthday this year in October, his exceptional musical gifts – as composer, award-winning pianist and conductor – cannot be contained, or pigeon-holed, into just one work, no matter how many times it is heard, or has been varied by the composer in factoring the considerable number of requests from different musical groups for performing versions based upon that single memorable theme. A creative mind that brought forth the theme (and harmony) that became ‘Walking in the Air’ cannot be gainsaid when other ideas and their varied applications and working suitabilities arise, especially when it is that very theme which has given rise to myriad commissions and fresh compositions.

In the preceding paragraph I mentioned Blake’s gifts as a pianist, which has also given rise to an exceptional body of original work.

WITH MANY MUSIC EXAMPLES

The Organ Music of Marie-Joseph Erb (1858-1944): Part I

William Melton

Family lore traced the ancestors of the Alsatian composer Marie Joseph Erb back to the twelfth century:

Originally from Graffenstaden, they were vidâmes of Strasbourg, then, from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century, knights attached to Rathsamhausen. They were lords of the Waldsberg near Mont Sainte Odile, then Stettmeister and senators in Strasbourg, sometimes honoured by this city, sometimes fighting against it.

What is conclusively documented is that the family had been organists in Strasbourg since the eighteenth century. It was there that the composer was born on 23 October 1858 to Anne Marie Erb, née Herrmann, and Marie Georges Erb, who was the director of the École St Jean and the organist of the Church of St Jean (built in 1477). The organ on which the father played (of twenty ranks, two keyboards and pedal), and the son began under his father’s tutelage, was originally built by Stiehr and Mockers in 1820 and enlarged in 1878 by Heinrich Koulen.

A formative musical event in Marie Joseph’s youth took place on 22 June 1863, when his father brought the five-year-old to the first local rehearsal of L’Enfance du Christ conducted by its composer, Hector Berlioz. The boy’s reaction to hearing the work performed with a massive 500-voice chorus is not recorded, but shortly afterwards Berlioz shared the audience response to the performance with his friend Humbert Ferrand:

The Royal Collegiate Church of St Katherine by the Tower

Charles William Pearce

This formerly stood about 350 yards from the Tower of London, just outside the City boundary. Founded circa 1148, by Queen Matilda, wife of King Stephen, as a Hospital or Alms house, the stately church consisted of an ante-chapel (or western transept somewhat like that of Peterborough Cathedral) and choir; the former six feet long (from west to east) and 60 ft. wide (from north to south), the latter 63ft. long by 32 ft. wide. The height from floor to roof was 49 ft. Built throughout in the Gothic style, the choir resembled that of a cathedral, both as regards spaciousness and ritual arrangement of stalls. In 1824 the church was pulled down, and the collegiate establishment removed to some new buildings erected (from the designs of Poynter) near Gloucester Gate, Regent’s Park. The present establishment (which remains as it ever was an ecclesiastical foundation) is governed by a Chapter, which consists of the Master (the Rev. A.L.B.Peile) three brethren, and three sisters with a chapter clerk and organist. The brethren must be in Holy Orders, and they stand in the same relation to the Master as Cathedral Canons stand to their Dean. The priests not only take their turn in preaching in the chapel, but also devote themselves as far as possible to helping in the Diocese; one of their number, the Rev. G. Brett (who died in 1906) did some excellent work in connection with the Diocesan Preventive and Rescue Association.

WITH FULL SPECIFICATIONS OVER THE YEARS

St Bartholomew the Great, London

Charles William Pearce

The old churches of London naturally divide themselves into two classes – those which escaped the Great Fire of 1666, and those which did not. Happily, the grand old Norman pile of St. Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield, belongs to the former class. The story of its formation is a romantic one. Rahere, who in 1103 founded both the Priory and the Hospital of St. Bartholomew, was a musician. A man of humble birth, he nevertheless succeeded by his wit, humour, and minstrelsy in becoming ‘a welcome companion of nobles, and a guest at the Court of King Henry I.’ Presumably, he made much money by the exercise of his many accomplishments. But, repenting him of the vanity of this kind of life, he made a pilgrimage to Rome; there dreamed a wonderful vision of St. Bartholomew, and as a result of his ‘conversion’, returned to his native land, and founded in Smithfield this church and priory of Augustinian Canons.

The Augustinian Order being famous for its medical skill and learning, the foundation of the hospital followed as a natural sequence. By March, 1123, the Priory Church was partially completed, and the choir (which is all that now remains) was consecrated by Richard of Beauvais, Bishop of London. What we now see of St. Bartholomew’s is of an older style of architecture than that of the Temple Church. In 1133 the church was finished, and King Henry II granted to the priory the privilege of holding a three days’ fair for the sale of cloth in the precinct still called Cloth Fair.

WITH FULL SPECIFICATIONS OVER THE YEARS

Henry Hackett FRCO (1872 – 1940) Organist and Composer

Robert Matthew-Walker

The music of organist and composer, Henry Hackett FRCO (1872-1940), is having something of a resurgence. Championed by leading London based organist David Cook, last year’s 150th anniversary of Henry Hackett’s birth prompted renewed interest in his life and works. Henry Hackett was a regular contributor to The Organ, including ‘The Organs and Organists of Leicester Cathedral’ (Vol. XIV, April 1935) and to Musical Opinion. Henry Hackett’s name has a place in the history of these illustrious publications.

This short article is an introduction to a longer article to be published in The Organ later this year. Both are written by Nigel Hackett, one of Henry Hackett’s two grandsons on behalf of the family and with the insightful contribution of David Cook.

Henry Hackett was born in Smethwick, Staffordshire to Mary H J Camm and John Hackett. The family was gifted artistically with Henry’s cousins Thomas, William and Florence Camm noted stained glass artists and his brother, Albert, also a professional organist.

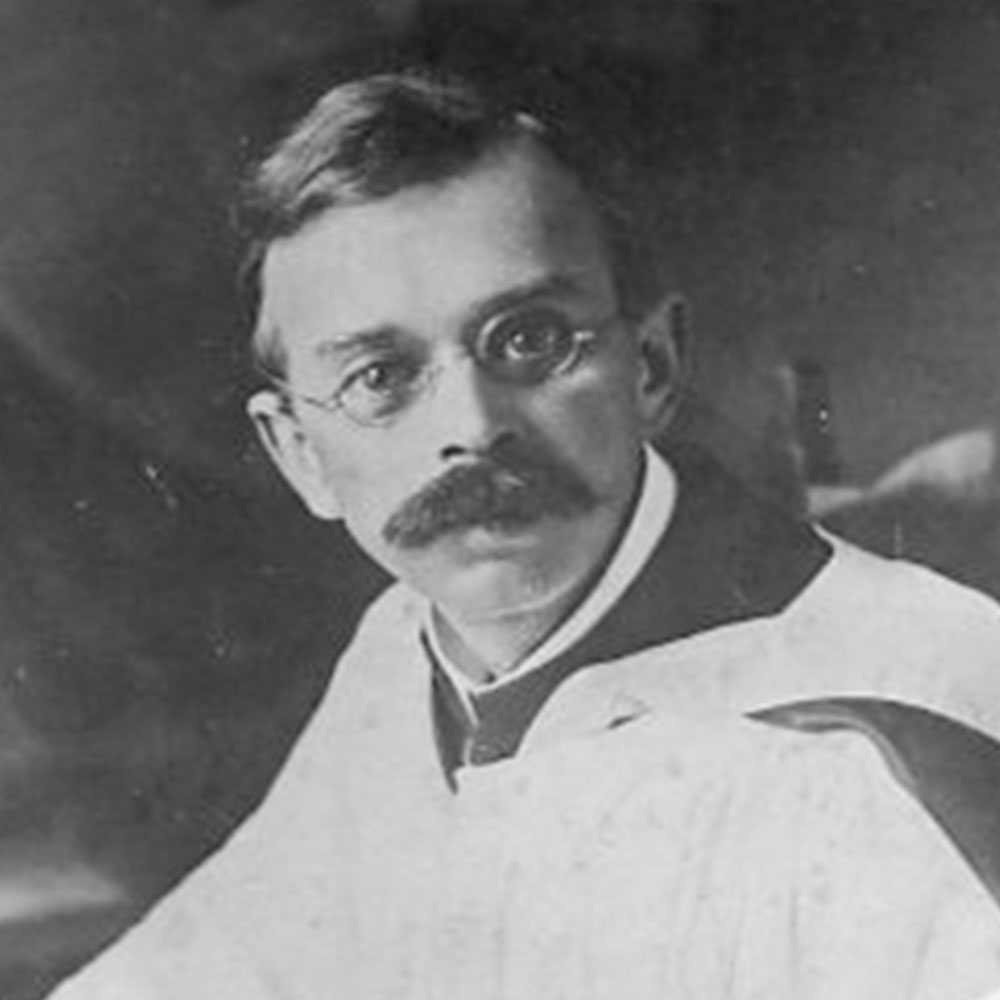

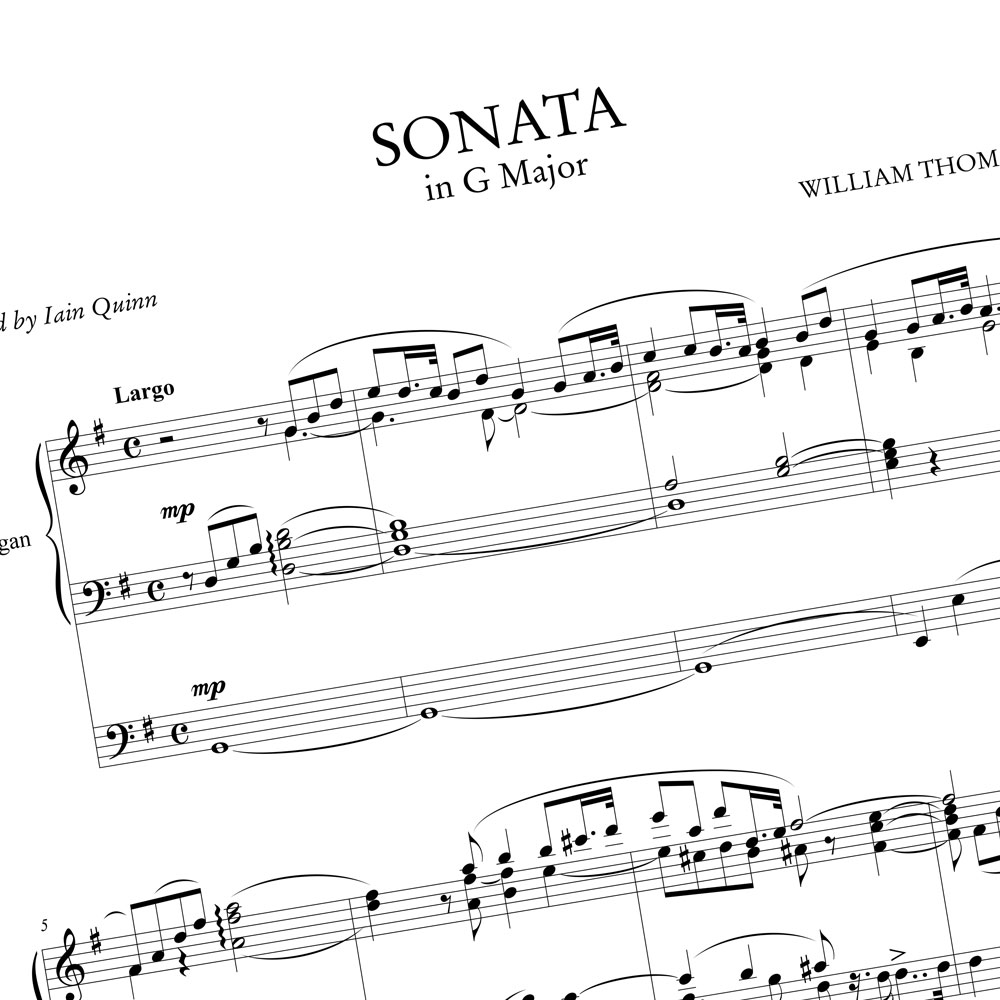

The Organ Sonatas of W.T.Best and William Spark - two masters of English organ music from thee mid-Victorian era

Professor Iain Quinn

The organ sonatas of William Thomas Best and William Spark are the earliest examples of English organ sonatas and mark the advent of a tradition that continues with little interruption until the mid-twentieth century. Although the exact dates of composition are unknown it seems likely that Spark’s Sonata was written in 1858 and Best’s Sonata in 1862. The date of the Spark is more certain because the cover of the first edition states that it was performed at a music festival in Leeds Town Hall in September, 1858. However, it is also possible that both were written earlier. The cover of the Best refers to him working at Wallasey Parish Church where he was appointed in 1860. However, that does not preclude the possibility that he wrote it some years before and published it later.

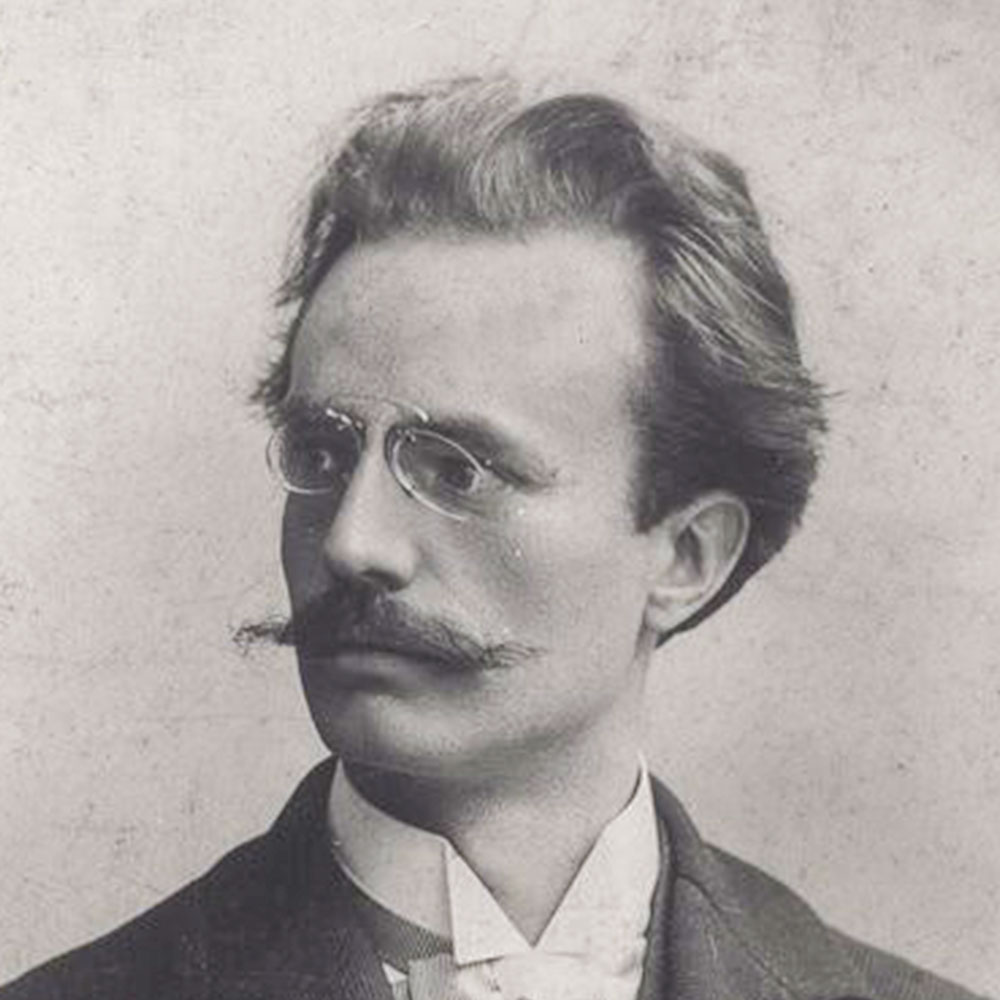

William Thomas Best (1826-1897)

“Had he been a long-haired Pole, or a lean and lanky Paganini, reams of paper would have been spoilt, and pints of good printers’ ink spread, in the public setting forth of his virtues and vices both moral, social, and professional.” (Orlando Mansfield, “W. T. Best: His Life, Character, and Works”, The Musical Quarterly,

vol 4, no 2, 1918).

Customarily known as W. T. Best, the most famous organist of St George’s Hall, Liverpool was born in Carlisle. He took early organ lessons with Abraham Young, the cathedral organist, but was otherwise largely self-taught, most likely learning the rudiments of organ technique from Johann C. H. Rinck’s method.