Current Issue

News

L’Orgue Baroque en Aragon

Jusepe Ximénez: Obra de Ileno de Premier Tono; Sacris Solemnis/Garcia Baylo (?), Pedro Pifant? (1473): Vexilla Regis/Andrés de sola: Registro alto de Primer Tono/Melchar Robledo: Domine Iesu Christe/Sebastián Aguillera de Heredia: Tiento grande de Cuarto Tono; La...

Westminster Abbey organ scholar Carolyn Craig appointed Junior Fellow at RBC

American organist and organ scholar of Westminster Abbey, Carolyn Craig has been appointed Junior Fellow at Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, part of Birmingham City University. She will take up the appointment in January 2024. Originally from Knoxville, Tennessee, and...

Registration organ competition IMOCG 2024 is open

The third edition of the Dutch 'International Martini Organ Competition Groningen' (IMOCG) will take place in the summer of 2024, in the week of 28 July to 3 August in the Dutch town of Groningen. This time, the competition will feature three monumental organs. After...

In Memoriam Peter Dickinson

Peter Dickinson died at the age of 88 on June 16, led a distinguished multifaceted career of over six decades as performer, academic, author and editor. His prolific writings and his compositional oeuvre in many genres radically espouse the postmodern aesthetic at the...

The International Kaija Saariaho Organ Composition Competition

The International Kaija Saariaho Organ Composition Competition, organised to celebrate Helsinki Music Centre Concert Hall’s new Rieger organ that is to be finished in the autumn of 2023, received 98 participating compositions from all over the world. The jury, chaired...

National Schools Singing Programme Expansion

The leading choral education programme in the United Kingdom expands to tackle declining engagement with music at state schools. Recently, the National Schools Singing Programme [NSSP], an ambitious music education initiative covering the majority of the UK’s Catholic...

Northern Ireland International Organ Competition Returns to Armargh: August 21-23, 2023

The 11th Northern Ireland International Organ Competition (NIIOC) will take place in Armagh from 21–23 August 2023, returning to the cathedral city where it was founded for the first time since the pandemic. The competition jury will be chaired by the Canadian...

Woman Composer Repertoire Day – Come and Sing

The Royal School of Church Music (RSCM) and Society of Women Organists (SWO) are hosting a joint Come and Sing event, showcasing new music written by female composers, on Saturday July 15 at St Giles Cripplegate, London EC2Y 8DA. The workshop is led by Katherine...

Applications invited for the UK’s first prep School pipe organ scholarships

Salisbury Cathedral School is proud to announce the launch of a new pipe organ scholarship programme, the first in a UK preparatory school. The new ‘Griffiths Chapel Organ Scholarships’, will support two organ scholars during Upper Prep, school years 7 and 8,...

Jens Korndörfer appointed associate professor of organ at Baylor University from August 2023

Jens Korndörfer leads a busy career as performer, educator, and church musician; he has performed to critical acclaim at prestigious venues and festivals such as Davies Symphony Hall in San Francisco, the Montreal Bach Festival, the Cathedrals in Washington, Berlin,...

New Director of Music appointed at Jesus College

Benjamin Sheen has accepted the post of Director of Music at Jesus College, Cambridge. He will join the College on 1 January 2023, succeeding Richard Pinel, who has been appointed Director of Music at St Mary’s Bourne Street in London. Ben currently holds the post of...

Bach and friends organ series

Details of Bach and Friends: The Orgelbüchlein Completed series presented by the Royal College of Organists and sponsored by Professor Christopher Wood. This will comprise the following ten events: Saturday 24 September 2022 Temple Church, 10am - ‘Laws and Canons’...

Cathedral organists rejoice in newly installed Woodstock practice organ

A two manual Vincent Woodstock practice instrument has been installed in the Song School at Peterborough Cathedral. The organ was constructed in 2011 and became available when its owner, Simon Johnson, moved from his role as Organist at St Paul’s Cathedral to become...

A new starter instrument for the United Kingdom: The Keyboard Studies Programme Melodica

It is no secret that music education in the UK has suffered as a result of cuts in budgets, and the pandemic has only further reduced opportunities for British children to engage with music. It is vital that music education survives in schools, if not for the...

Visually Impaired Teenager Wins Prestigious Musical Scholarship

Sixteen year old Ivan Deb has won the first Aprahamian Scholarship for young organists which includes a brand new two-manuals-and-pedals home organ, on which he can practise. The Arabesque Trust, which set up the scholarship to help visually impaired young organists,...

Explore By Topic

Autobiographical Recollections of Charles-Marie Widor

Autobiographical Recollections of Charles-Marie Widor

Edited and translated by John R. Near

Boydell and Brewer / University of Rochester Press, 2024

ISBN 9781648250866 / 298 pp / £85 (hard copy), £25 (ebook)

Reviewed by Robert James Stove

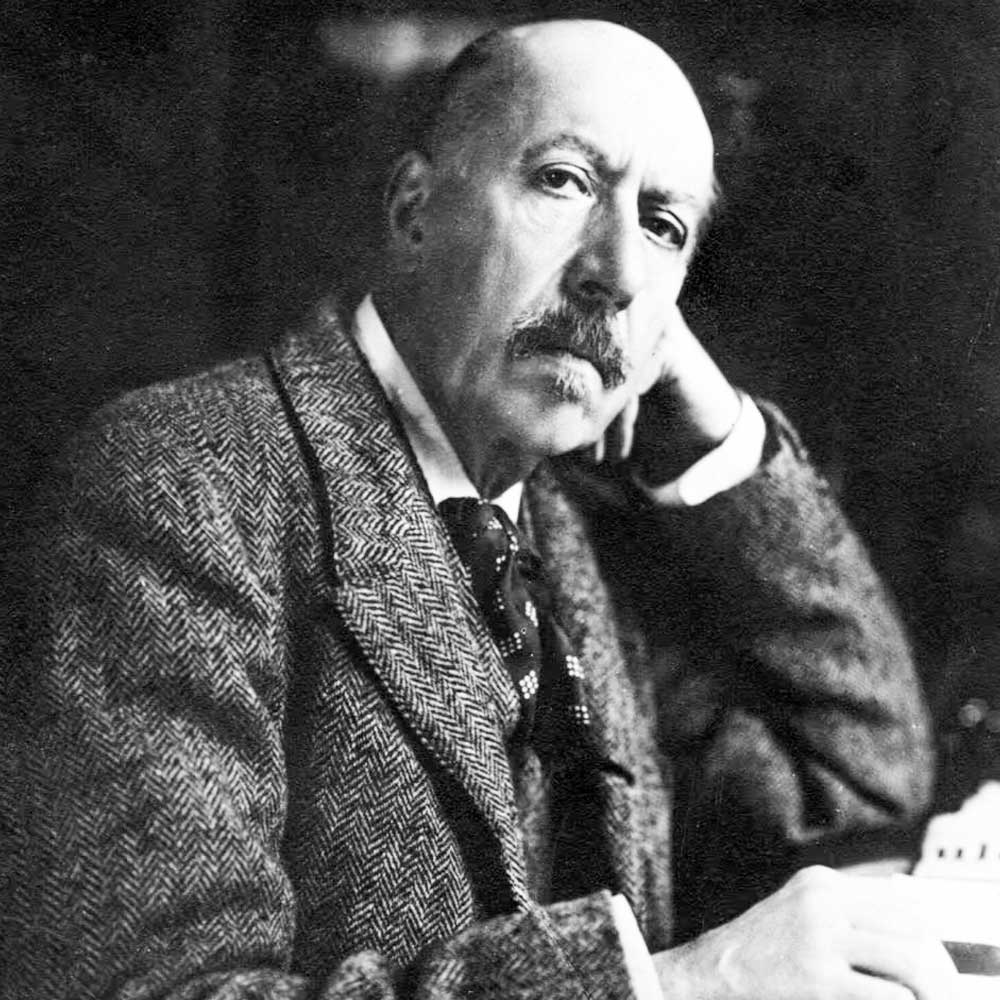

Brash to the nth degree will be the reader who is not awed into at least temporary deference by this book’s cover design: from which stares the haughty, craggy visage of the septuagenarian Widor himself, as severe and impassive as any Easter Island statue, and with his dotted cravat alone implying amiable human emotion. A similar profound, if less overwhelming, awe should govern readers’ response to John R. Near’s pertinacious research.

No other musical master owes as much to one specialist’s efforts as Widor does to Professor Near’s. In addition to producing the definitive biography of his subject (Widor: A Life Beyond the Toccata, 2011), and more recently assembling Widor’s didactic prose (Widor on Organ Performance Practice and Technique, 2019), Professor Near has supplied indispensable critical editions of Widor’s organ symphonies, correcting abundant errors that plagued original print versions. Envisage a parallel universe where Ernest Newman had not only written his four-volume account of Wagner, but been compelled to edit each Wagner opera from the autograph: this analogy alone can hint at the magnitude of Professor Near’s endeavours.

He began these endeavours at a time when, on the share-market of musical opinion, stocks in Widor – and in the French Romantic organ school generally – had crashed. ‘We don’t play Widor here,’ sniffed the head of organ studies at Professor Near’s own New England Conservatory: ‘you know, he really didn’t write good music.’ Such Podsnappery echoed the verdict of Hungarian-American musicologist Paul Henry Lang, who in 1941 dismissed Widor’s organ symphonies (had he ever heard them?) as ‘contrapuntally belaboured products of a flat and scant musical imagination, the bastard nature of which is evident from the title alone.’ If Lang’s assessment no longer wins over undergraduate hearts and minds, we have Professor Near’s efforts above all to thank for the change.

In 1936 (the year he turned 92), Widor dictated the Souvenirs on which the present volume is based. Only one copy of the 103-page document survives: Jeanne Dupré, widow of Marcel Dupré, found it in her husband’s papers. It came into the possession of Widor’s grand-niece, Marie-Ange Guibaud, who enabled Professor Near to use its contents when he worked on the 2011 biography.

These contents engendered certain problems. Widor’s memory, though exceptionally retentive, played on him the occasional trick. Now and then his amanuensis, Édouard Monet, simply spelled a name wrong or left a blank that now cannot be filled. But the chief difficulty lay in the extreme breadth of Widor’s erudition; on every page he alluded to artistic and political figures who, albeit celebrated in 1936, will mean little or nothing to most readers almost a century afterwards. Herein is the book’s most remarkable achievement. Fully half of the present volume consists of Professor Near’s own endnotes, which lighten our darkness, making the crooked straight and the rough places plain to an extent that, if he had published nothing else in his life, would itself cause him to shine among modern scholars.

It is, on the whole, a rather mellow Widor who emerges from the Souvenirs. He allows himself the occasional peppery rebuke – his chief target being Vincent d’Indy, safely dead since 1931 – but the politicking zest of his younger self (which included his public humiliation of Paris Conservatoire director Théodore Dubois) had faded. Whether through genuine late-onset benignity or through a prudent memento mori, he told at least one interviewer after revealing a controversial tale: ‘Keep this to yourself.’ Still, readers will hardly feel oppressed by excessive blandness. Widor’s capacious mind so abounded in anecdotes which sometimes dated back to France’s Second Republic (1848-1851), and his career had introduced him to so many notabilities from Edward VII, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Portugal’s Luís I, and John D. Rockefeller Junior downwards, that he merely needed to keep talking to remain interesting.

And in words, scarcely less than in notes, the style was the man. Although in many respects Widor’s career is unimaginable outside France, no-one partook less of vulgar chauvinism. Like Richard Strauss, he recognised only two sorts of people: the gifted (whatever their national origins) and the ungifted. If the organ-loft mentality exists outside the preconceptions of the organ’s ill-wishers, Widor never lapsed into it. When he looks back, he takes at least as much pride in his operas, ballets, and chamber works – some of which are now creeping, not before time, into discographies – as in his output for the King of Instruments. His role as cultural bureaucrat formed a liberal education in itself, bringing him in touch with France’s outstanding painters, sculptors, and authors as much as with its composers. Of narrow factional prejudice in his own art, he seems to have been almost wholly devoid (who else could have numbered among his admirers Saint-Saëns and Debussy?). Royal and imperial courts, however glamorous, instilled in him a respect that never degenerated into toadying. He speaks with particular esteem of Alfonso XIII, whom he found generous, charming, and intelligent: a finding almost universal among those who knew Spain’s unfortunate monarch in the flesh, rather than merely deriving their misinformation about him from newspapers’ gossip-columns.

Only near the end did Widor’s formidable stamina seep away from him. Professor Near quotes a sorrowful account by his pianist friend Isidor Philipp of a 90th-birthday concert at Saint-Sulpice, which Widor insisted on conducting himself, despite a podium technique which Philipp called ‘mediocre, uncertain, timid.’ Desperately, Philipp writes, ‘he insisted upon going on to the end. … After the concert he was led fainting to his car.’ Yet he rallied, to Philipp’s own astonishment. A lesser nonagenarian would have been rendered prostrate by the news in November 1936 that Madrid’s Casa Velásquez, the cultural centre to which Widor had devoted so much activity and money, suffered terrible bombing damage during the Spanish Civil War. Not Widor: ‘If our dear Casa is destroyed, we will rebuild it.’ Four months later he breathed his last, having assured the faithful Dupré: ‘I cannot complain, I have had a beautiful life.’

One finishes examining Autobiographical Recollections with renewed awareness of how well Widor fits Berlioz’s epitome of Meyerbeer: ‘he had not only the luck to be talented, but the talent to be lucky.’ Widor recounted how, when Big Bertha directed its fire at Paris during the 1914-1918 war, he and his colleague Charles Waltner happened to be strolling along the Pont des Arts, ‘in the wonderful moonlight at midnight. The whistle of a bomb grazed our ears and I said to Waltner, “Hey, that was meant for us!” [Eh, mais, c’est pour nous!].’ Had the ammunition come a few centimetres closer to the great man … the resultant loss to French music hardly bears thinking about.

====================