Peter Dickinson died at the age of 88 on June 16, led a distinguished multifaceted career of over six decades as performer, academic, author and editor. His prolific writings and his compositional oeuvre in many genres radically espouse the postmodern aesthetic at the interface between serious and popular music styles, and he pioneered American music studies in British universities.

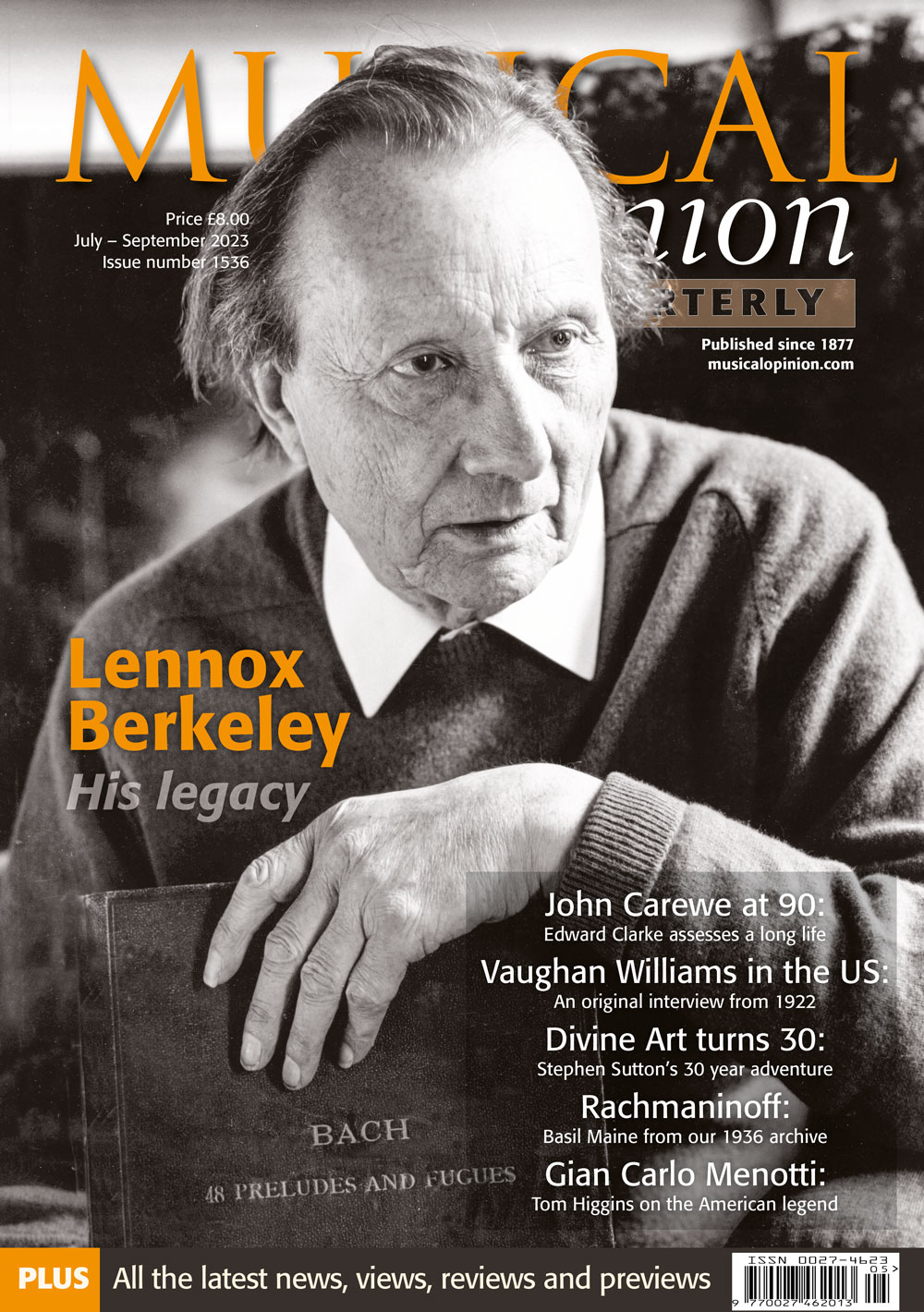

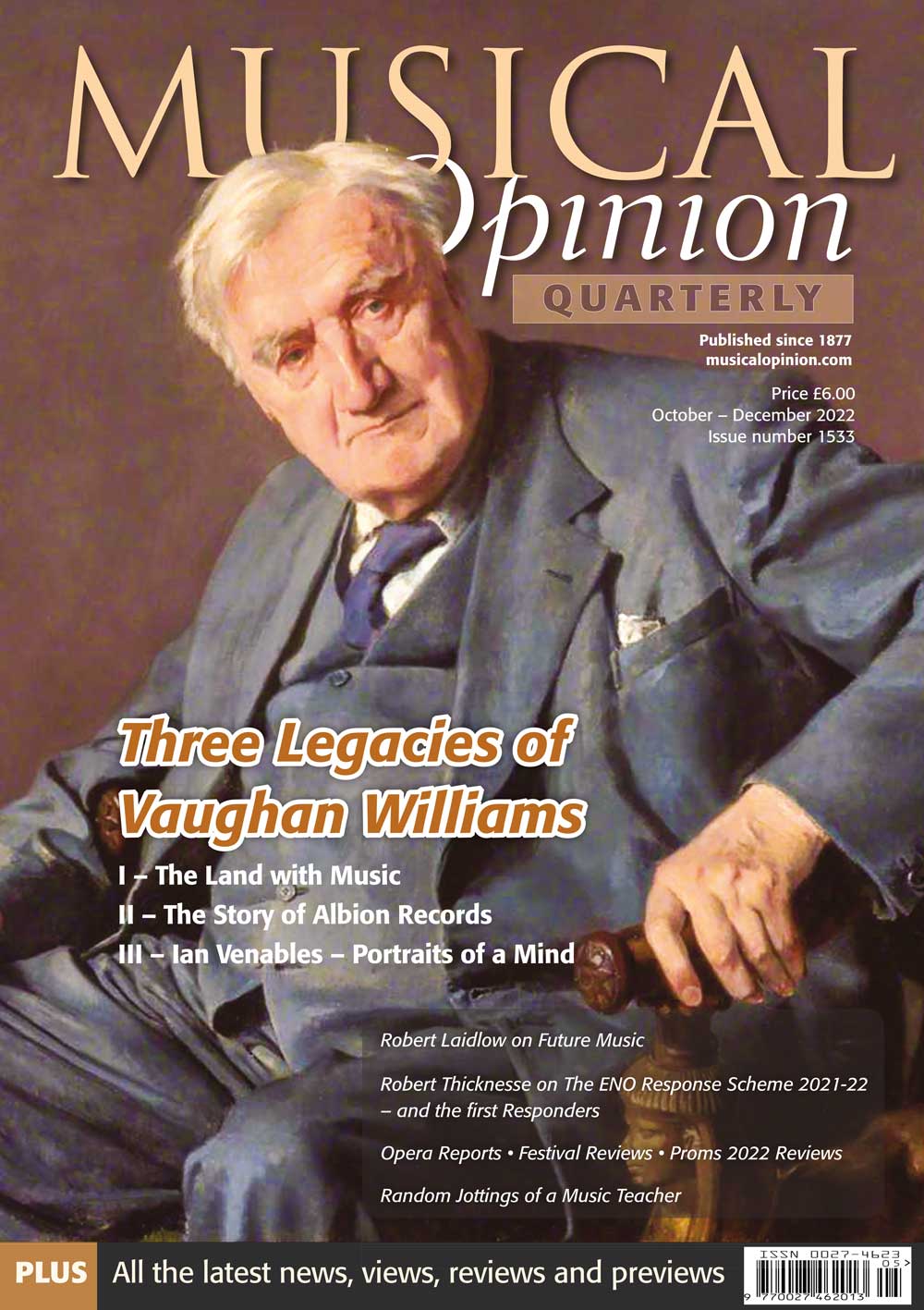

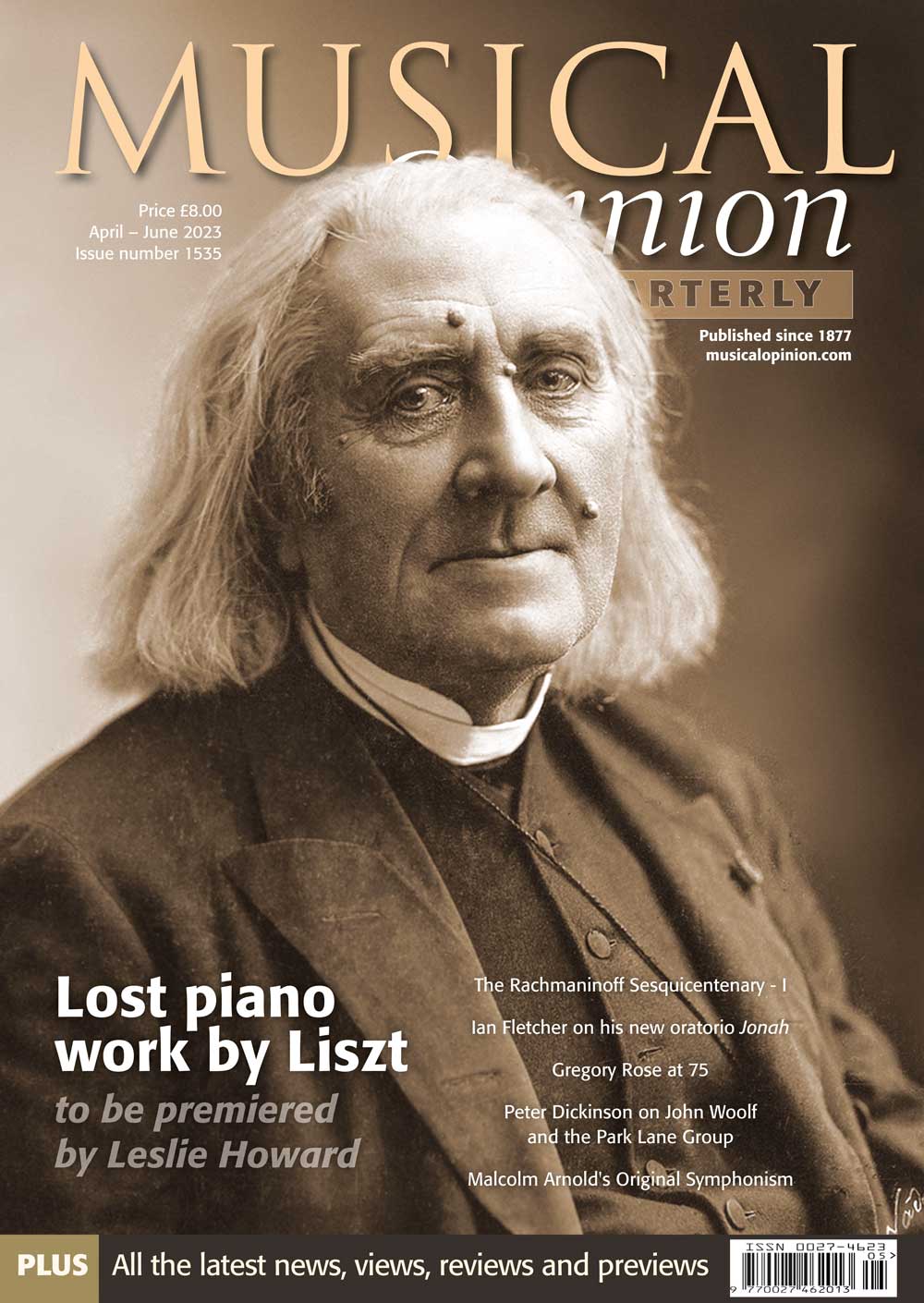

He studied at Queen’s College Cambridge, where he was organ scholar and student of Philip Radcliffe, receiving advice from Lennox Berkeley. A Rotary scholarship enabled him to pursue his studies at the Juilliard School with Bernard Wagenaar. Whilst in New York he was pianist with the New York City Ballet, reviewed concerts and encountered luminaries such as Cage, Cowell and Varese, gaining first-hand experience of the American avant-garde. The love of American creativity infused his later work in Britain, where he forged a new sub-discipline of American music studies at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. After a period teaching at the College of St Mark and St John in Chelsea (1962), and a lectureship at Birmingham university (1966-70) he was appointed first professor of music at Keele university where he founded its Centre for American Music, receiving an hon. DMus in 1999. Following a period as Chair at Goldsmiths College (1991-7), he was appointed Fellow and head of music at the Institute of United States Studies (1997–2004), London University, setting up an MA in American Music and presenting lecture and concert series. A board member of several societies and charities, he was chair of the Rainbow Dickinson Trust for music education, editing several volumes of the educational theories of Bernarr Rainbow. His contribution as a writer on modern British, European and American music, includes ground-breaking volumes on key figures in Twentieth century new music and experimentalism, Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, John Cage, Lord Berners, and the first ever monographs on Lennox Berkeley and Billy Mayerl.

Dickinson’s scholarship is reflected in his overarching tendencies as a composer. His oeuvre covers an eclectic mixture, ranging across atonal pointillist Modernism, and popular styles such as neo-baroque jazz, ragtime and blues. He developed a technique he termed ‘style modulation’, about which he published essays, connecting him with the modern and post-modern composers who, like Ives, Berio or Schnittke, have drawn creatively on past traditions creating collage-like tapestries. It is especially telling in Dickinson’s Mass of the Apocalypse, composed for the 300th anniversary of St James’s Piccadilly, premièred there in 1984, a modern masterwork challenging conventional boundaries. Part Mass and part Music Theatre, its five movements alternate choral mass texts with narrated extracts from the Book of Revelation set to contrasting idioms, dramatic choral ‘muttering’ at the start, a rhythmic ‘rock’ beat in the ‘Sanctus’ and ‘Benedictus’, atmospheric hushed soundscapes in the ‘Agnus Dei’ and a joyous Bernsteinesque ‘Gloria’, the surprising conclusion a dark, mystical meditation. Many works were composed for specific performers; Translations, for recorder gamba and harpsichord, for instance, was conceived in 1971 for David Munrow, Oliver Brooks and Christopher Hogwood, pioneers of the early music movement. Some works overtly evoke an American idiom, of Ives and Barber, as in his American Trio (1985), commissioned for the Verdehr Trio and the unfinished opera The Unicorns (1967) to a libretto by John Heath-Stubbs. His output covered one opera, Judas Tree (1965), concertos for organ (1971), piano (1984) and violin (1986), much choral, vocal, chamber and keyboard music. It is heartening to know that he lived to see many of his works released on CD bringing works from the early 50s to the most recent years across many genres, performed by leading artists, for instance the organist Jennifer Tate. As an accomplished pianist he appeared on several of these CDs of his works, including the most recent, made in 2021 during the pandemic crisis, entitled ‘Lockdown Blues’. He partnered major soloists, notably the violinist Ralph Holmes and oboist Sarah Francis, as well as his sister, the singer Meriel Dickinson with whom he toured over several decades, writing songs and cycles for her.

Both Dickinson’s music and writings represent individual, thoughtful and sometimes radical responses to the influences and currents around him. From his earliest period, in New York and later in Europe, he would encounter and write about luminaries like Bernstein and Stravinsky, Virgil Thompson, Nadia Boulanger, as well as WH Auden and Philip Larkin, whose poetry he set. He often wrote occasional works, like the Waltz for Schwartz (2016) conceived as an 80th birthday tribute for the American composer Elliot Schwartz.

His own 80th birthday concert in November 2014, held privately in central London, was an aptly festive occasion which I was fortunate to attend, having known him and reviewed his music over many years. Peter’s sparkling songs and piano music performed by young talented PLG musicians, intertwined with works Dickinson has performed, recorded or written about – Copland, Berkeley and Satie, in the presence of the composer and his family, his sister Meriel, friends and colleagues, including notable performers, composers and critics. Responding to the special cake brought in by the late John Woolf, PLG Director, Peter sat at the piano and proceeded to regale the entire assembly with delightful encores of his own versions of Duke Ellington standards, spiced by his own harmonic embellishments. It is in this happy mood of spontaneous music-making that I would like to recall him, radiating joie de vivre with warmth and wit, radiating his unique personality, ever supportive of and interested in others, always ready to share a pearl of wisdom or witty anecdote.

Like his personality, his writing was notable for its clarity, elegance and cultural breadth. In myriad reviews, articles and chapters he confronted and navigated the swirling cross currents of the music of the 20th and 21st centuries. An anthology of his collected writings, aptly titled Words and Music, published in 2016 shortly after his 80th birthday, bears an impressive introduction by British music expert Stephen Banfield, who eloquently celebrates Dickinson’s achievements as a composer, his eclectic output constituting a rich legacy for future generations. Dickinson’s remarkable contribution as both creative force and cultural commentator enriches our own and future generations. Our thoughts are with his wife Bridget and their entire family. He will be sorely missed by friends, colleagues, students and public alike.

Peter Dickinson’s writings include the first book on Sir Lennox Berkeley (Thames 1989, much enlarged 2nd ed. Boydell 2003); a study of the popular pianist-composer Billy Mayerl (OUP 1999); Copland Connotations: Studies and Interviews (Ed. Boydell 2002); CageTalk: Dialogues with and about John Cage (University of Rochester Press 2006/enlarged paperback 2014); Lord Berners: Composer – Writer – Painter (Boydell 2008, paperback followed) and Lennox Berkeley and Friends: Writings, Letters and Interviews (Boydell, 2012). Peter Dickinson: Words and Music (Boydell 2016).