Suite de Pièces pour Violon et Orgue

Previous Issues

Spring 2024. 408

Winter 2024. 407

Autumn 2023. 406

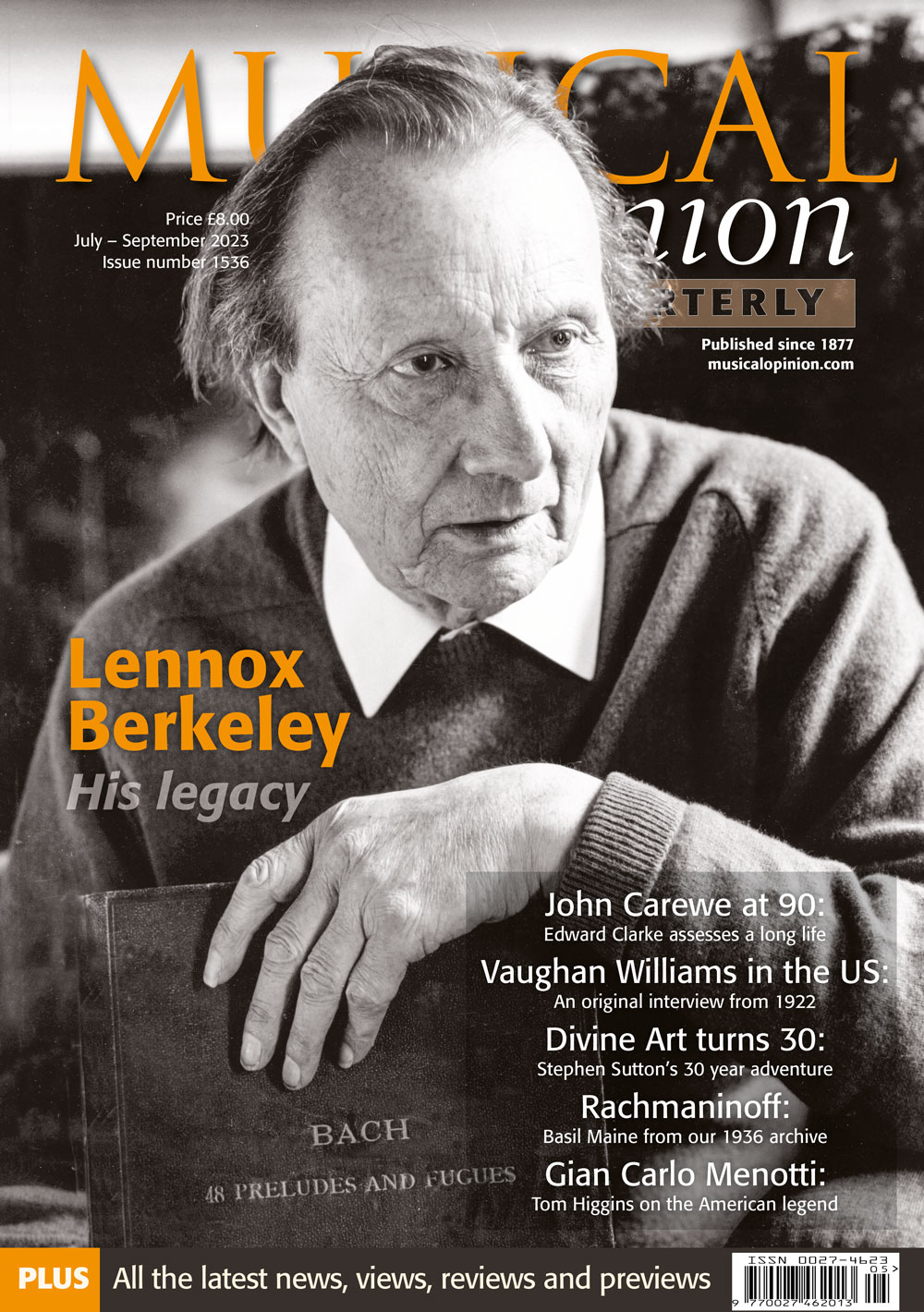

Summer 2023. 405

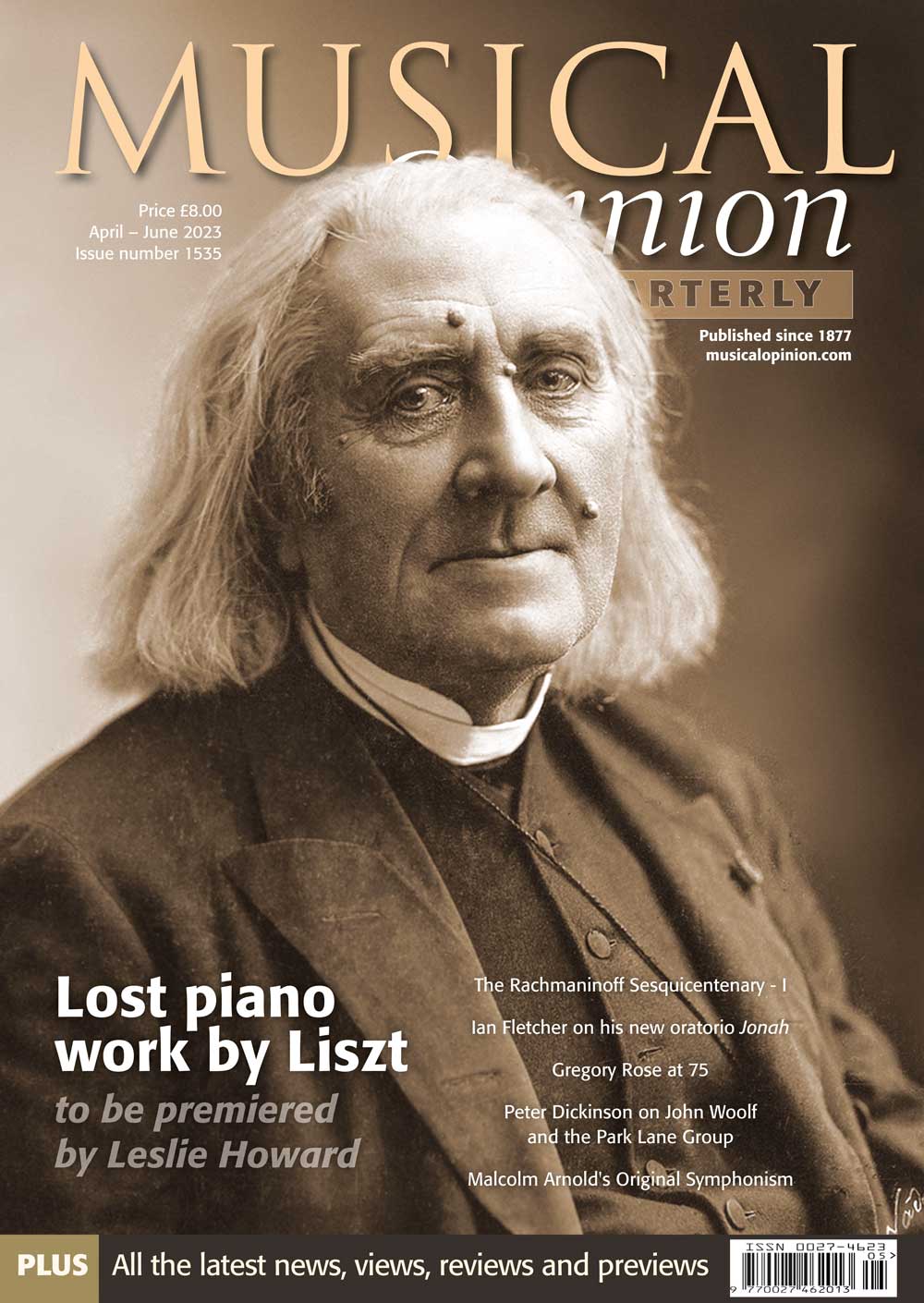

Spring 2023. 404

Winter 2023. 403

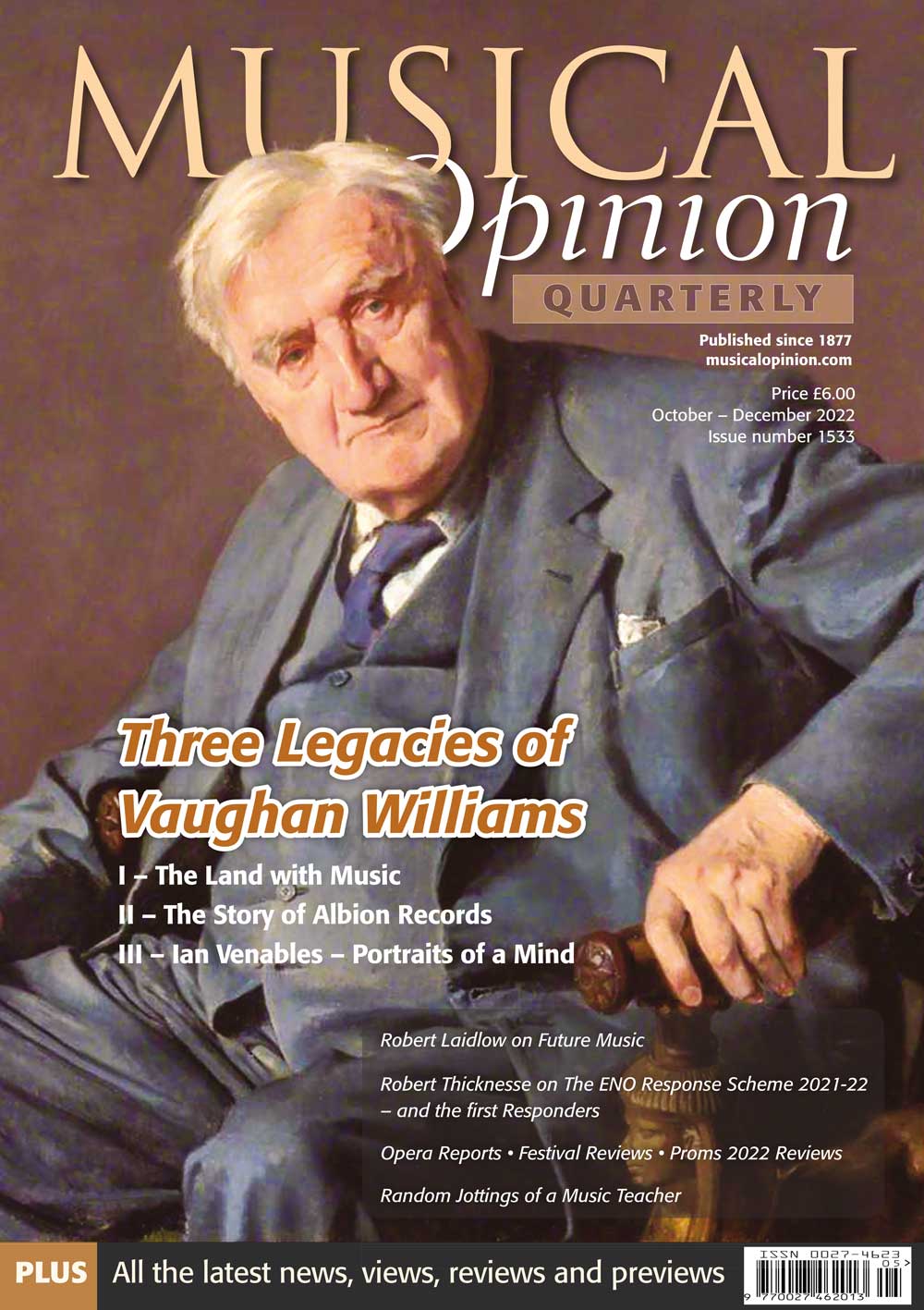

Autumn 2022. 402

Summer 2022. 401

Spring 2021. 400

Winter 2021. 399

Autumn 2021. 398

Whilst staying at A4 size and 56 pages, the magazine has been completely redesigned with different fonts (more easy to read), bigger photopgraphs, more focus on things like specifications and more CD reviews of organ repertoire.

Summer 2021. 397

Winter 2021. 395

Spring 2021. 396

Autumn 2020. 394

Summer 2020. 393

Spring 2020. 392

Winter 2019. 390

Autumn 2019. 389

Explore By Topic

Autumn 2024. Issue 410

The Music of Joaquín Niin-Culmett

Martin Anderson

Joaquín Nin-Culmell’s refined and elegant music points to the gentle equanimity of his character rather than to his disruptive childhood; he seems to have suffered far less from it than did his elder sister, the writer Anaïs Nin. Their father, the composer-pianist Joaquín Nin y Castellanos (1878–1949) was born in Cuba, like their mother, the singer Rosa Culmell, but grew up in Barcelona. Nin-Culmell’s parents were living in Paris when Anaïs was born, in 1903; a second child, Thorvald, later to become a businessman, followed in 1905, and in 1908 Joaquín was born (on 5 September) in Berlin, where his father had moved to try to further his career. In 1909 Nin tried – and failed – to launch a national opera in Cuba and then retreated with his family to sulk in the outskirts of Brussels. Three years later the immature and exploitative Nin despatched wife and children to his parents in Barcelona and moved to Paris, abandoning his family to pursue his abusive peccadillos in the French capital. Photo: Wikimedia

Notes on the life of Marcel Dupré

Harold Fabrikant

Marcel Dupré was one of France’s greatest musicians in the twentieth century and without doubt the most famous French organist of his time.

He died in Paris, aged 85, in 1971, caving played (and improvised, as usual) for Mass that morning. His student life was brilliant and his rise as international concert organist meteoric, starting in London in 1920 and in New York the next year. His ninth and last American trans-continental tour occurred in 1948–49, when he played in fifty cities. No young man then, he continued giving concerts in Europe until autumn 1970.

At that time the general public had a seemingly insatiable appetite for concert organ music and organ building flourished to keep pace with the demand. Cleveland’s public auditorium, for example, an opulent twentieth-century edifice, seated 13,500; Ernest Skinner provided a 5-manual organ of 146 stops which was opened in 1922. Photo: Wikimedia

Two Roman Instruments

Dr Michał Szostak

In May and September 2024, I had the pleasure to perform recitals at two marvellous and historically important sacral buildings in Rome: St Peter’s Pope Basilica Outside the Walls (Basilica Papale di San Paolo fuori le Mura) and Pantheon (Italian: Basilica of Santa Maria ad Martyres). Both instruments do not represent the highest standards of musical instruments we could expect in such prestigious venues; however, it is worth taking a closer look into the history and features of both places and organs.

The construction of organs in Italy has a long and distinguished history, shaped by the unique aesthetic, liturgical, and technical traditions that emerged throughout different periods. Italian organ building remained relatively stable in its fundamental design from the Renaissance well into the late Baroque period, with several core characteristics that distinguished it from developments in other European countries. According to organ historian Hans Davidsson, the Italian organ typically featured a single manual, rarely included pedalboards with independent stops, and emphasised a clear, light tone with a foundation of principal stops known as the “ripieno”. These stops provided a consistent tonal base, contrasting with the more diverse, heavily reeded sounds favoured in French and German organs during the same period. Photo Dr Michał Szostak

All Hallows, Lombard Street

Charles William Pearce

The six city churches dedicated to All saints were all called by the old English name, All Hallows. Very much concealed by houses, the interesting church named above is approached from Lombard Street by a gateway leading into a passage through the houses which opens onto a small churchyard. As the east end of the church adjoins the houses on the west wide of Gracechurch Street, Stow and others call is by the name of ‘All Hallows, Gracechurch’. Mention is made of this church as early as 1053 in the Monasticum Anglocanum: the rectory then, as now, being in the gift of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Rebuilt between the years 1494-1544 (when the steeple was finished) the church was entirely destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, and afterwards rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren at a cost of £8,058 15s 6d. The ground plan of the present building is that of an oblong without aisles, the tower being situated at the S.W. angle within the plan. The dimensions are: length, 84 ft., breadth, 53ft., height of roof, 30ft., height of tower, 85ft. The tower contains ten bells, brought from the unhappily demolished church of St Dionis’ Backchurch in 1879. Photo: Wikimedia

Recent Editions of 18th century English Organ music – including a tribute to David Patrick on his 90th birthday

John Collins

Over the past few decades there has been an increase in well established publishing houses such as OUP, Novello, Hinrichsen, Faber and A-R editions publishing organ compositions by British composers of the period from ca.1725-1840, sometimes including compositions from the 16th and 17th centuries, with editors including Robin Langley, Gwilym Beechey and H. Diack Johnstone, producing reliable texts with an informed introduction and a critical commentary. These were mainly selective anthologies with relatively few volumes devoted to an individual composer. The three volumes edited by Geoffrey Cox with a good selection including less well known pieces published as volumes 1-3 of the Faber Early Organ Series of European organ music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, now sadly out of print, and the 10 volumes English Organ Music- an anthology from four centuries in ten volumes – edited by Robin Langley for Novello offering a far greater appraisal of the English repertoire from the 16th through to the early 17th centuries also included one volume devoted to concertos and one to duets.

Prior to these C.H.Trevor had produced six volumes of Early English Organ Music for OUP, which covered from the 16th to the early 19th centuries and included some complete voluntaries as well as many movements extracted from multi movement compositions. Photo: Fitzjohn Music

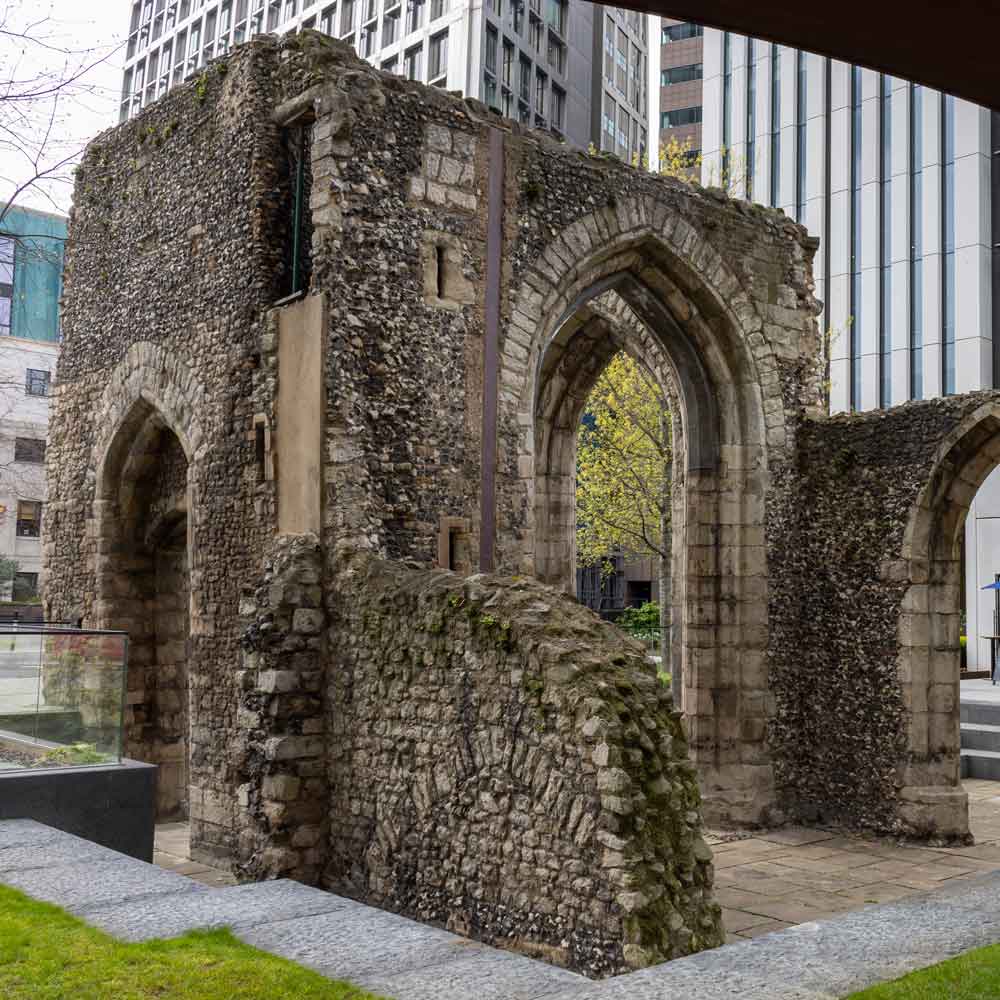

St Alphege, London Wall

Charles William Pearce

This unpretending structure is to be found on the south side of the street known as ‘London Wall’. Its east front is to be seen in Aldermanbury. The Anglo-Saxon saint to whom the church is dedicated, St. Alphege (variously called Alphage, Alfege, Alphy or Elphage) was Bishop of Winchester, 984-1005, and was afterwards translated to Canterbury. He was martyred by the Danes at Greenwich in April 19th, 1015; upon which day he is now commemorated in our present Prayer Book Kalendar. Stow tells us that the first church in London to be dedicated to St Alphege, stood ‘near unto the wall of the city by Cripplegate.’ The site now occupied by St Alphege Church was then covered by the priory or hospital of St Mary the Virgin, founded in the year 1332, by William Elsing, for canons regular, the founder being the first prior. When this religious house, valued at £193 5s. 6d., was surrendered on May 11th, 1529, to Henry VIII, the south side of the priory church was converted into the parish church of St Alphege; the older parish church nearer the wall being pulled down, and its site afterwards used ‘as a carpenter’s yard, with saw-pits.’ This ancient south aisle escaped the great Fire, and was still standing in 1708, when Hatton described it as the then parish church of St. Alphege, London Wall. He said it was ‘partly of the gothic order, both the windows and pillars within the church. Length, 78 ft.; breadth, 42 ft.; altitude, 22 ft.; the tower is inconsiderable, being only about 40 ft high, but there are in it five bells which ring in peal.’ Photo: Freepik