Previous Issues

Summer 2024. Issue 409

Suite de Pièces pour Violon et Orgue

Winter 2024. 407

Autumn 2023. 406

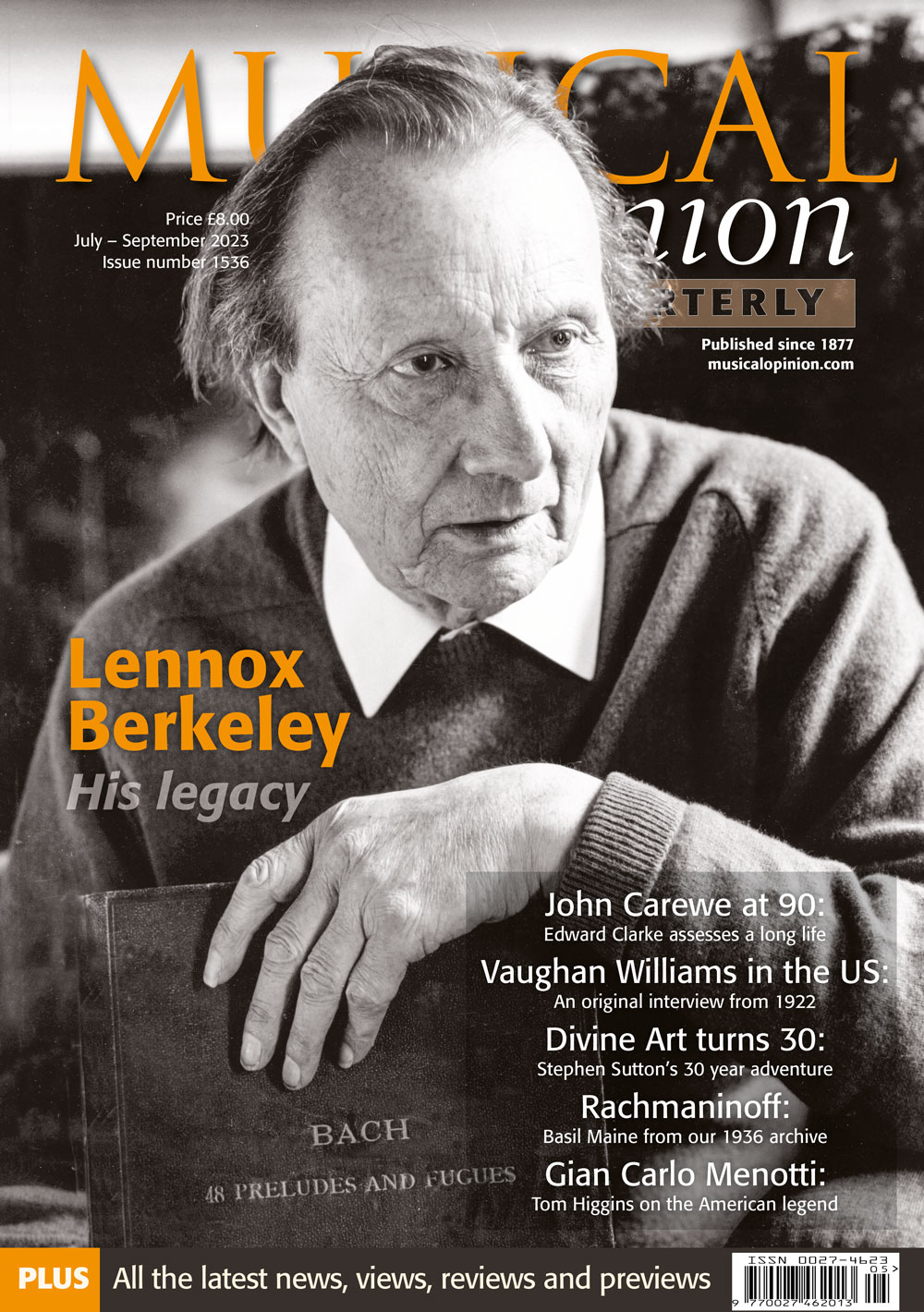

Summer 2023. 405

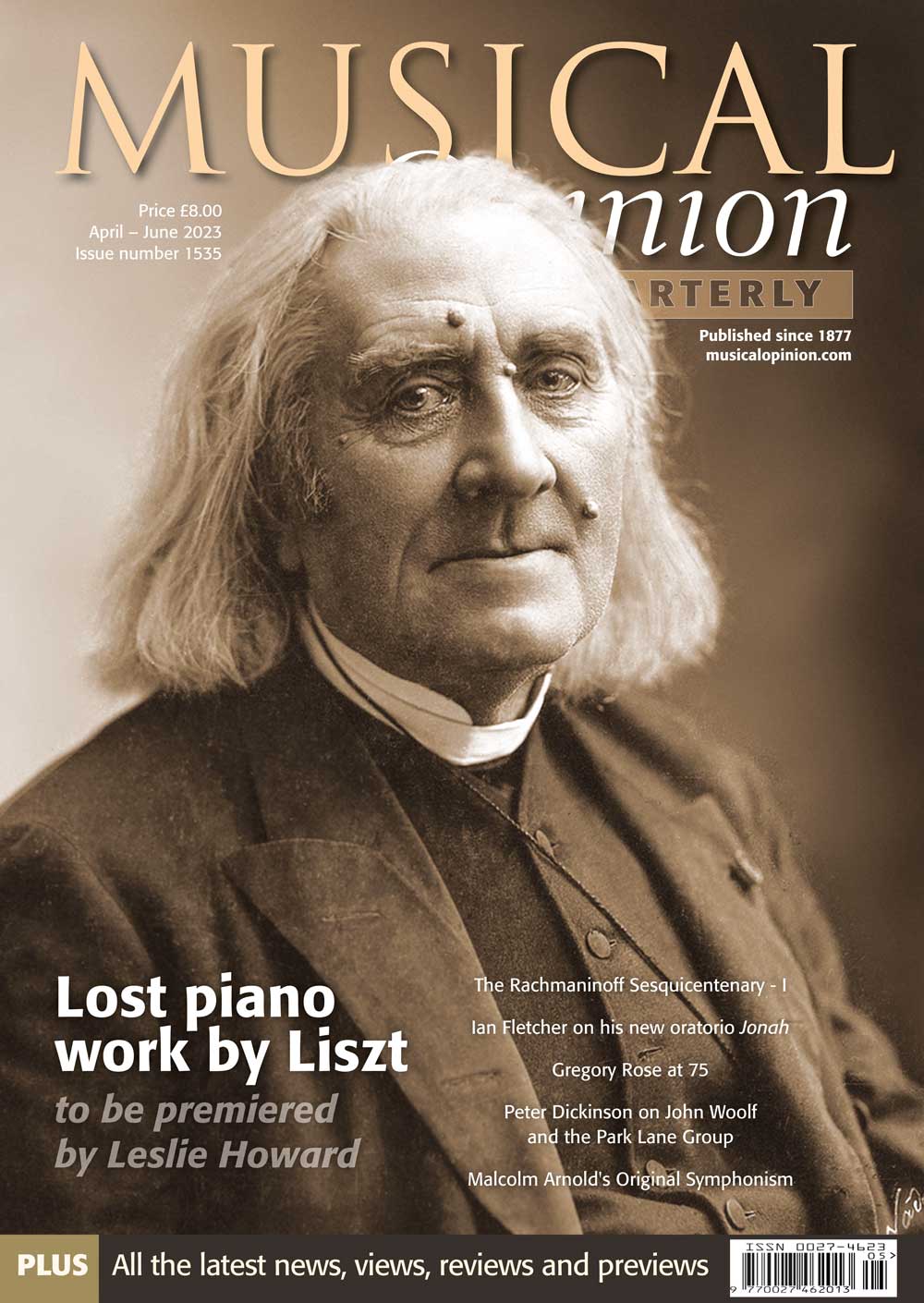

Spring 2023. 404

Winter 2023. 403

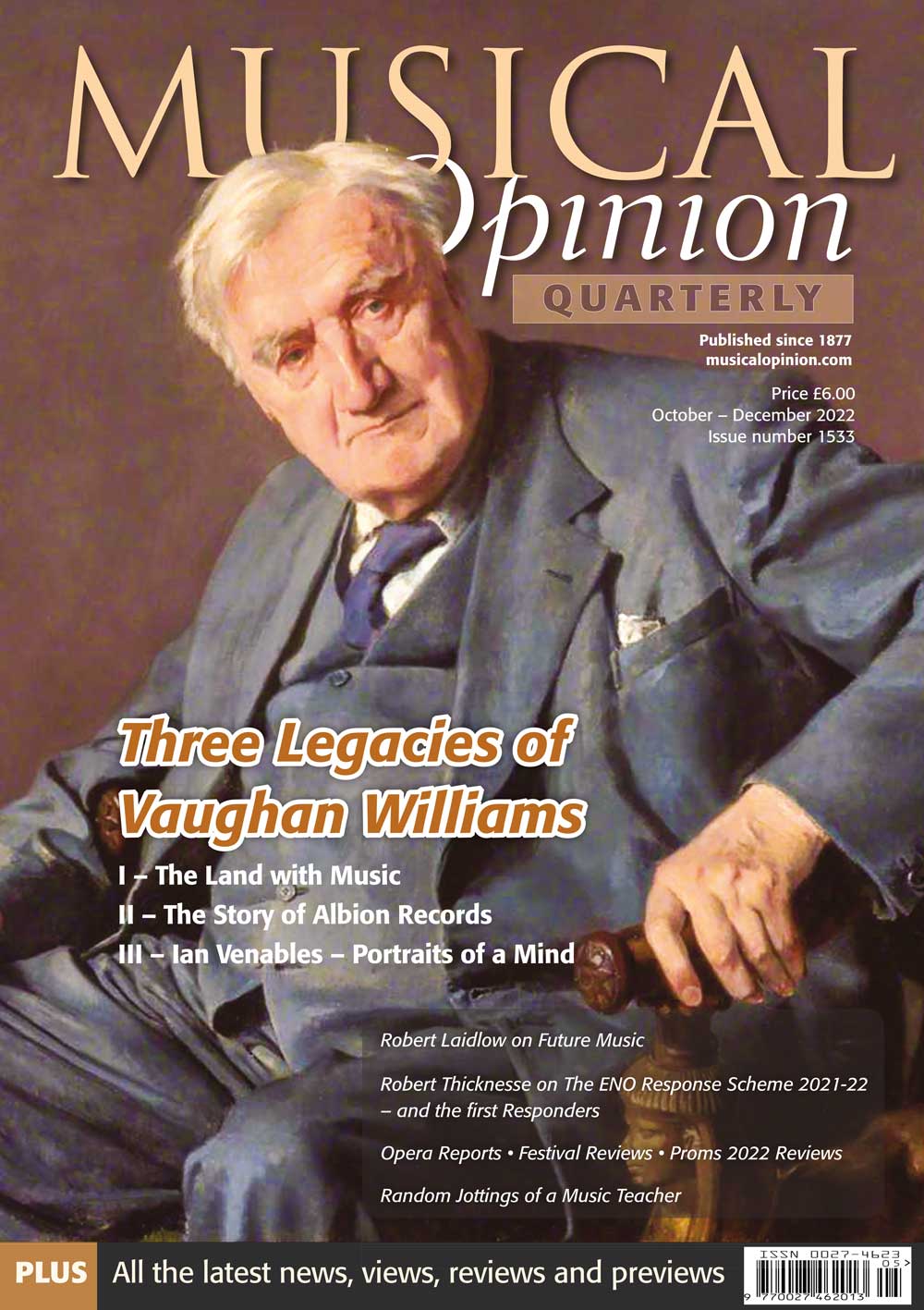

Autumn 2022. 402

Summer 2022. 401

Spring 2021. 400

Winter 2021. 399

Autumn 2021. 398

Whilst staying at A4 size and 56 pages, the magazine has been completely redesigned with different fonts (more easy to read), bigger photopgraphs, more focus on things like specifications and more CD reviews of organ repertoire.

Summer 2021. 397

Winter 2021. 395

Spring 2021. 396

Autumn 2020. 394

Summer 2020. 393

Spring 2020. 392

Winter 2019. 390

Autumn 2019. 389

Explore By Topic

Spring 2024. 408

Organ Music of the early 17th-century

John Collins

In this in-depth overview of a number of significant recent publications of organ music from the first half of the 1600s, our distinguished correspondent considers the nature of such compositions and the editorship required in making much of this music available to organists of the present day.

The 1620s saw a remarkable series of publications across Europe presenting the repertoire of an individual composer – Manuel Rodrigues Coelho in 1620, Francisco Correa de Arauxo, in 1626 Samuel Scheidt in 1624, Girolamo Frescobaldi and Johann Ulrich Steigleder, both in 1624 and 1627 and Jacques Titelouze in 1623 and 1626. This year, 2024, sees the 400th anniversary of the publication of three important collections of music for keyboard instruments, namely Il primo libro di Capricci by Girolamo Frescobaldi, the Ricercars by Johann Ulrich Steigleder and the massive Tablatura Nova, originally issued in three parts, by Samuel Scheidt. In the following article-review I shall look at the prints by Frescobaldi and Steigleder and discuss their importance, not just for their time, but also for us today.

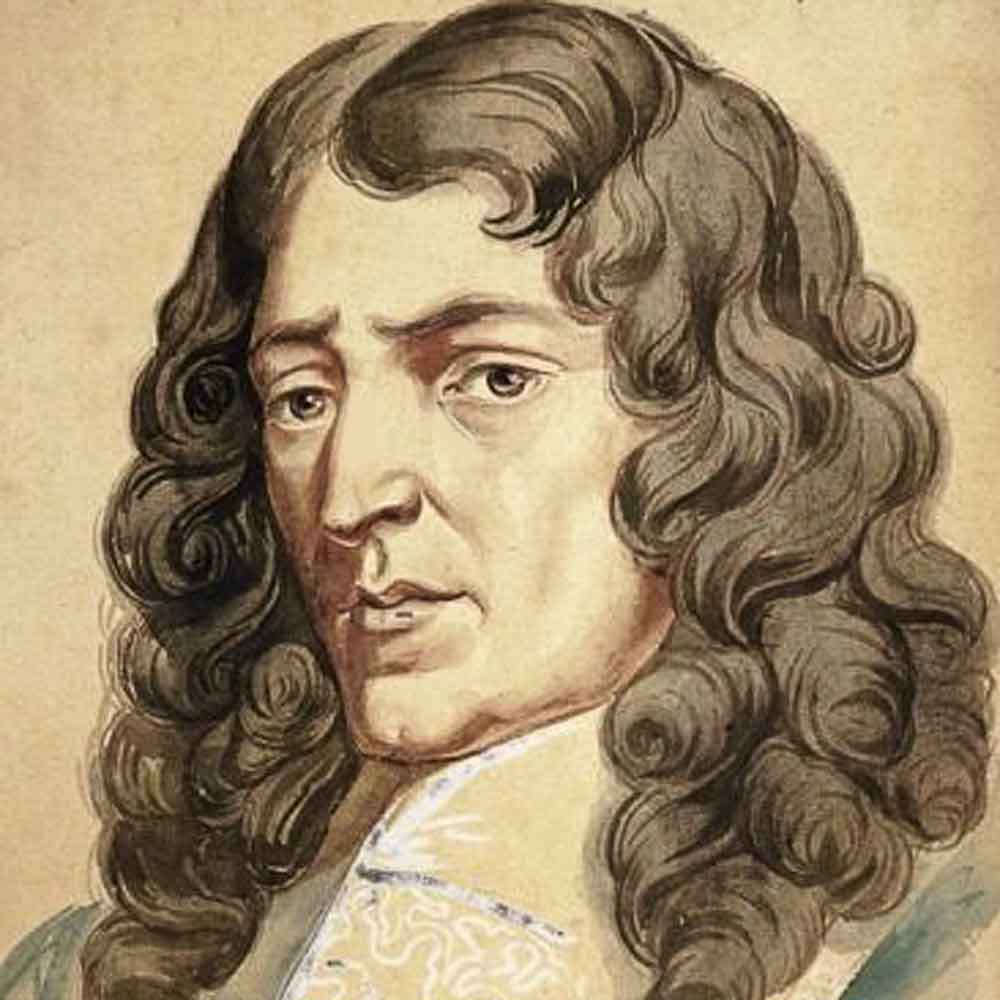

Girolamo Frescobaldi, 1583-1643, was organist at St. Peter’s Rome, and published seven collections of pieces for keyboard, embracing all genres, as well as chamber and vocal music. He established a formidable reputation as a performer and teacher, amongst his most successful students being Johann Froberger. Photo Wikimedia

Composers of Organ Music – Anniversaries in 2024

John Collins

In 2024 there are several composers for organ whose anniversaries can be commemorated, although some of the dates are not known for certain; some of the names listed below will need no introduction but there are also quite a few lesser-known names whose compositions are well worth exploring. No claim is made for completion, and there is no guarantee that every edition mentioned is in print – there may also be complete or partial editions by other publishers some of which may be difficult to obtain. Publishers’ websites have been given where known. Details of a small number of composers whose preserved output consists of only a few pieces have been omitted.

Giacomo Carissimi 1605-74. Organist of Tivoli cathedral, he published a large number of collections of sacred music and is believed to be the compiler of the organ method known as Wegweiser, which was published in Augsburg in 1689, the first part of which gives instructive notes on the rudiments of music, fingering, figured bass, information on clefs and the church Tones, The second part contains 71 pieces, comprising eight pieces on each of the eight Tones including a longer Praembulum followed by seven fugal verses – the final one sometimes being of a reasonable length. Pieces 65-65-69 give more pieces on the fourth Tone including a Fuga, Variatio, a Variata Fuga and a Finale. No. 70 is a Toccata in two sections on the second Tone, and the final piece is a Toccatina in several sections in B flat, including scales in contrary motion. Modern editions by Rudolf Walter originally as volume VIII in the series Suddeutsche Orgelmeister des Barocks published by Musikverlag Alfred Coppenrath, and now available through Carus Verlag 91.076/00, and Gwilym Beechey for Hinrichsen, Edition Peters 7164, which has a good introduction describing the print. Photo Wikimedia

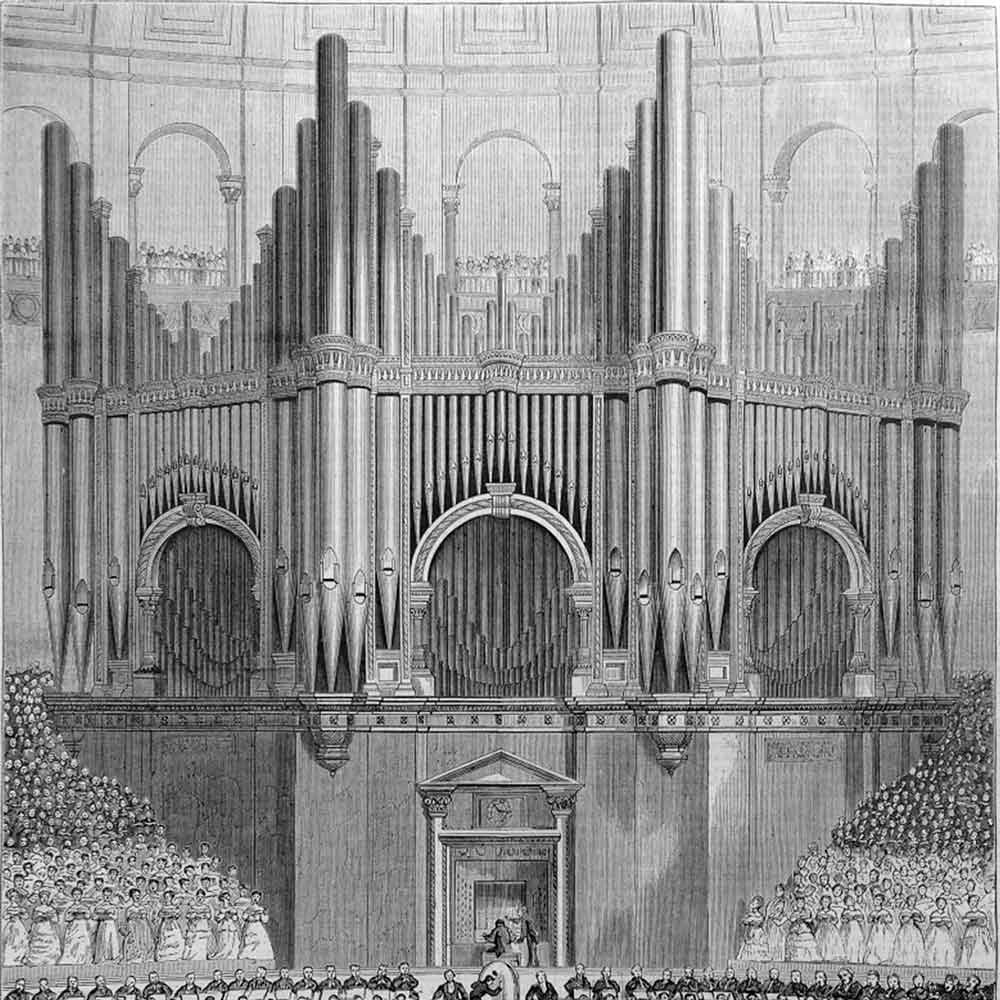

Bruckner’s Recitals in France and England

James Palmer

On the occasion of the bicentenary of the birth of Anton Bruckner, the author traces the composer’s visits to Nancy, Paris and London in 1869 and 1871.

Writing in The Musical Times in 1937, the distinguished Austrian-born British musicologist Mosco Carner outlined many aspects of the visits that Anton Bruckner made on two occasions during his lifetime to countries outside of his native Austria. At the outset, I should like to acknowledge Carner’s work on this subject, from which I have drawn, in shedding light upon an aspect of the composer’s life that – in this, Bruckner’s bicentenary year – continues to remain very little-known.

As Carner began, a somewhat curious aspect regarding Bruckner’s public organ recitals is that until World War II France and Great Britain were the only two countries in which Bruckner appeared as a concert organist, and yet were countries in which his music was known only to specialists and very few concert-goers. In various ways, of course, these were not the only countries in which Bruckner’s music had – up to that time – failed to appeal to the wider concert-going public. Photo Freepik

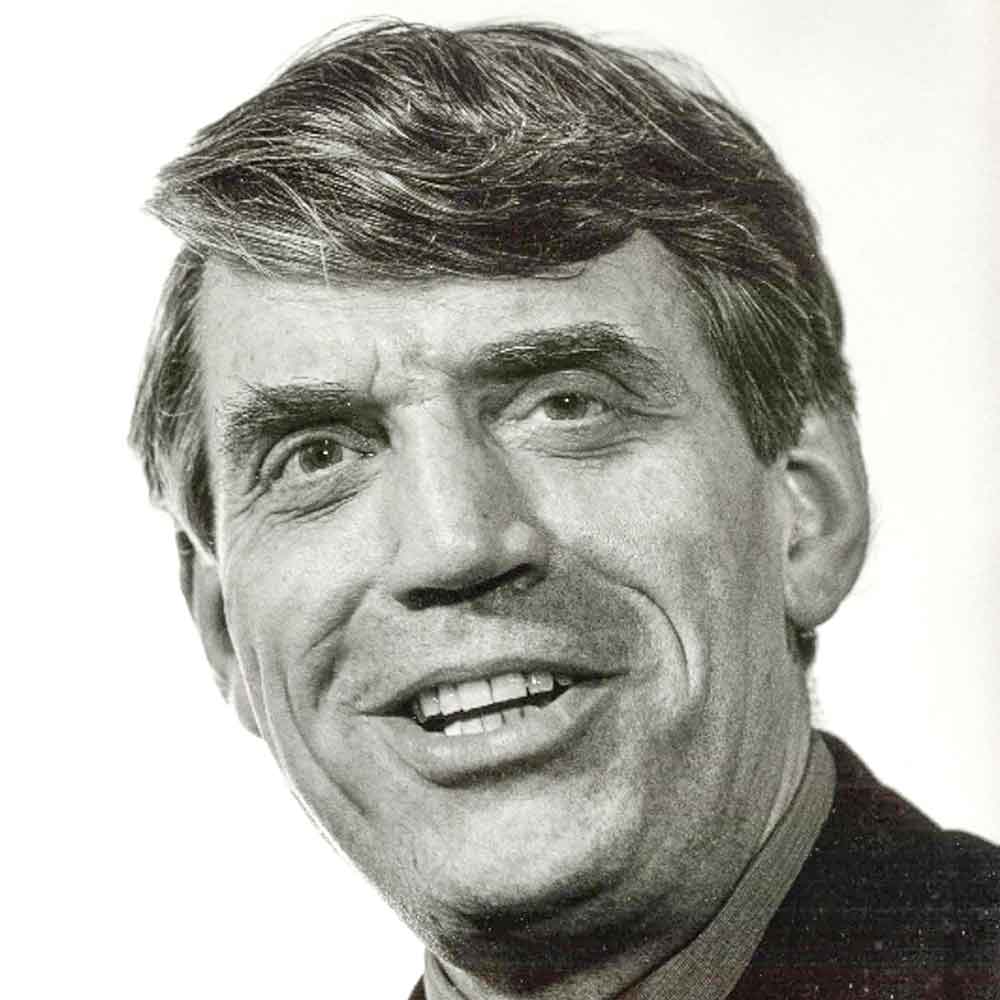

The Organ Music of John Gardner

Chris Gardner and Tom Winpenny

John Linton Gardner was born 1917 and grew up in the seaside town of Ilfracombe, in North Devon. His father, Dr Alfred Linton Gardner, was serving in the First World War as an army surgeon and was killed in his sleep in 1918 when an enemy shell landed on his farmhouse billet in France. Before the war, he had been the organist at Christ Church, Chelsea, while studying medicine, later working at Guy’s Hospital as a surgeon.

There is no doubt that John’s musicianship was encouraged and supported from an early age by his widowed mother, Muriel. She was a competent musician and, having married into a medical family, she determinedly steered John away from a career as a doctor and towards one as a musician. His early manuscripts, from the age of seven or so, survive and reveal rapid progress, with technical competence and artistic quality developing apace. Working his way through Eagle House School at Sandhurst, Berkshire, and then on to nearby Wellington College, where his place was supported by an army charity for the families of officers killed in action, he played cello in the orchestra, piano and organ, as well as composing prolifically and playing ‘rugger’ and cricket.

Walter Stanton, the Director of Music at Wellington, engineered Gardner an introduction with Hubert Foss, head of the Oxford University Press music division, then based in London. Foss was supportive, and accepted Gardner’s Intermezzo for publication – his first work to appear in print. Foss would go on to introduce him to such musical luminaries as William Walton and Arthur Benjamin, both of whom would play a small part in developing his talent as a composer. In 1997 Gardner wrote of Foss to Diana Sparkes, Foss’s daughter: ‘He is somebody I look upon as being absolutely crucial in getting me into a musical career. He was endlessly kind to me and it was a great tragedy for OUP when he left. It has never been the same since’. Photo John Gardner estate

Friedrich Lux – A composer of organ music outside of the canon

Jan Lehtola

Friedrich Lux (1820–95) is one of those composers whose names have been forgotten and who have only recently begun to receive the attention they deserve. Similar cases often come to light, and as part of my ongoing collaboration with Toccata Classics I have already ‘rehabilitated’ the music of William Humphreys Dayas (1864–1903), Richard Stöhr (1874–1967) and Eduard Adolf Tod (1839–72). Why do such composers fall into oblivion, even though their works are technically accomplished and abound in personal character, whereas others remain enduring favourites?

One reason is the concept of a ‘canon’ of repertoire, which in recent years has been widely criticised by music historians. A ruling musical canon – the sum of many factors – was gradually built up in the course of the nineteenth century. Its emergence was influenced by the Geschichte der europäisch-abendländischen oder unserer heutigen Musik by Raphael Georg Kiesewetter (1834) and, especially, the Geschichte der Musik (1862–78) by August Wilhelm Ambros. Other reasons were concert repertoires, national factors, the opinions of other historians and the views expressed in various component cultures. Rationalist classification and compartmentalisation have also influenced the way people think. In the 1970s ‘genre theory’ (Carl Dahlhaus, Tibor Kneif) was the common method of addressing music as a subject for research – but it is only a tool (admittedly a serviceable one) for rearranging that which is already recognised. Classification should not become a dogma; it must remain dynamic.

Why is it, then, that some composers acquire almost hallowed status? One reason is that the canon is seldom updated. Musicians generally prefer to play music that they know, and historians likewise gravitate to topics with which they are familiar. Photo Freepik

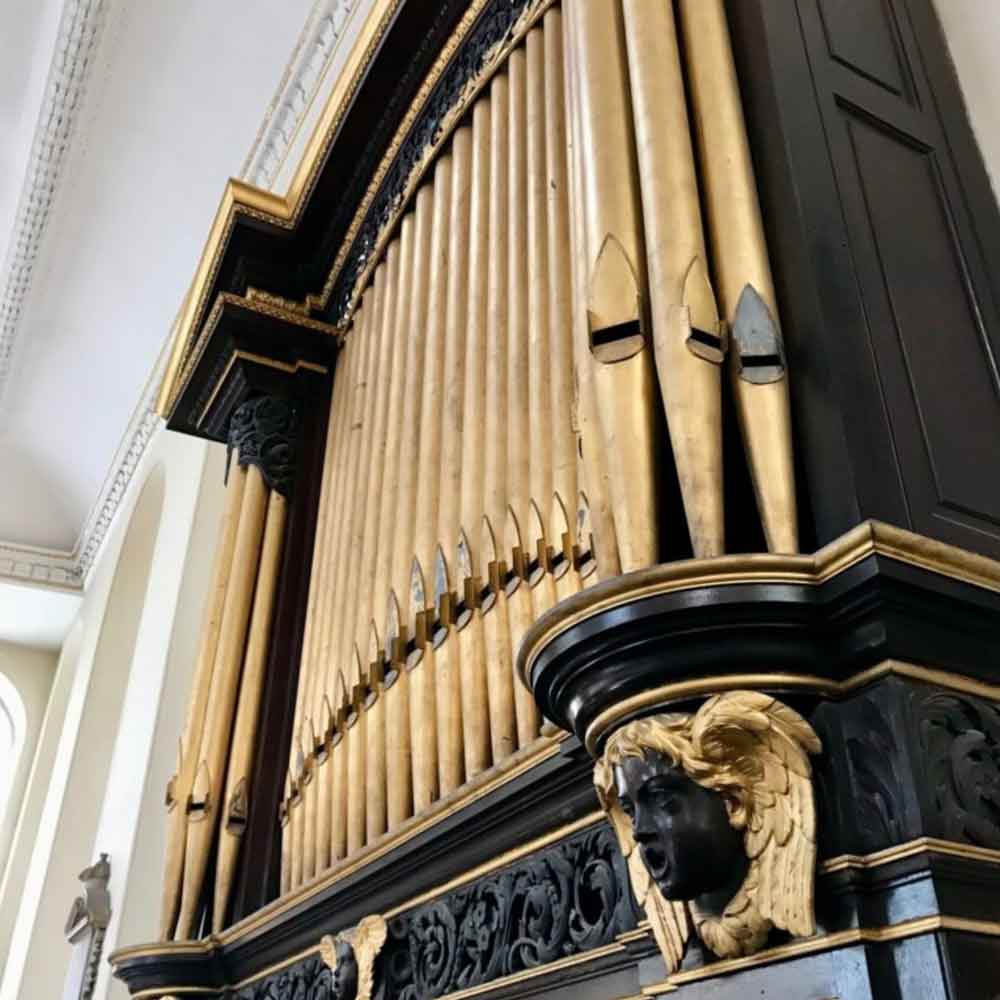

The Organs of Old London City Churches (1905) St Edmund the King, Lombard Street

Charles William Pearce

Stow says, ‘This church is also called St Edmund Grasse church, because the grasse market came down so low.’ Dedicated to the holy Saxon King Edmund (murdered by the Dances in 870, because he would not renounce the Christian faith), it probably boasts a high antiquity; there being several circumstances that point to the Saxon heptarchy. Nothing is known of the old church which was burnt in 1666. The present building (which, unlike any of Wren’s churches, is incorrectly orientated, lying north and south instead of east and west), consists of a nave without aisles or columns, a recessed chancel at the north end (ceiled in the form of a half-dome) and a tower (comprehended within the ground plan) at the south end. Completed in 1690, the church cost £5,207 11s., and its dimensions are: Length, 69ft.; Breadth, 39ft.; Height, 32ft. The south front (which is the only portion of the church visible from the street) lies a few feet behind the houses on each side of it; on this narrow strip of land in the early part of the last century there was a shop built on one side of the principal entrance, and a watchhouse on the other. The church was ‘restored’ by William Butterworth in 1864, and again in 1880. The patrons of the living are the Crown and the Archbishop of Canterbury. The organ is said to have been originally built by Renatus Harris, but was rebuilt by J.C.Bishop in 1833, and was than considered a characteristic example of the religious quality of tone for which Bishop was famous. Photo Wikimedia

Chicago’s Largest Colossus

Dr Michal Szostak

In March and April 2024, I undertook a Spring recital tour to the United States to perform at a few venues in Chicago, Illinois and San Francisco, California. The first stop on that trip was the Fourth Presbyterian Church in Chigaco, where in 2015, the Quimby Pipe Organs company built the most prominent instrument in the city and the whole Midwest. This article describes the church’s history (one of the largest in the city), the history of its instruments, the current organ and some fundamental facts about the organ-building company that created that colossus.

Nestled majestically along the bustling Michigan Avenue in Chicago, the Fourth Presbyterian Church is a testament to faith and architectural splendour. Since its inception in 1848, when it was founded as a congregation in the burgeoning city of Chicago, the church has served as a beacon of hope and worship for millions of individuals, with its iconic stone façade welcoming congregants and visitors alike.

The church’s journey began amidst the ashes of the Great Chicago Fire, which razed its original building to the ground in 1871. Undeterred, the congregation persevered, finding solace and communion in a new location at Rush and Superior until 1914. That year, the cornerstone for the current church, designed by the esteemed architect Ralph Adams Cram, was laid, marking the beginning of a new chapter in the church’s storied history. Photo Dr Michal Szostak

Cram, renowned for his Gothic revival style, infused the Fourth Church with a unique blend of English and French Gothic elements, resulting in a structure that exudes grandeur and grace. The imposing Bedford limestone walls, sourced from the same quarries as iconic landmarks such as the Empire State Building and the National Cathedral, lend a timeless quality to the church’s exterior, while the interior boasts intricate stained-glass windows crafted by Charles Connick of Boston.