Previous Issues

Autumn 2024. 410

Spring 2024. 408

Winter 2024. 407

Autumn 2023. 406

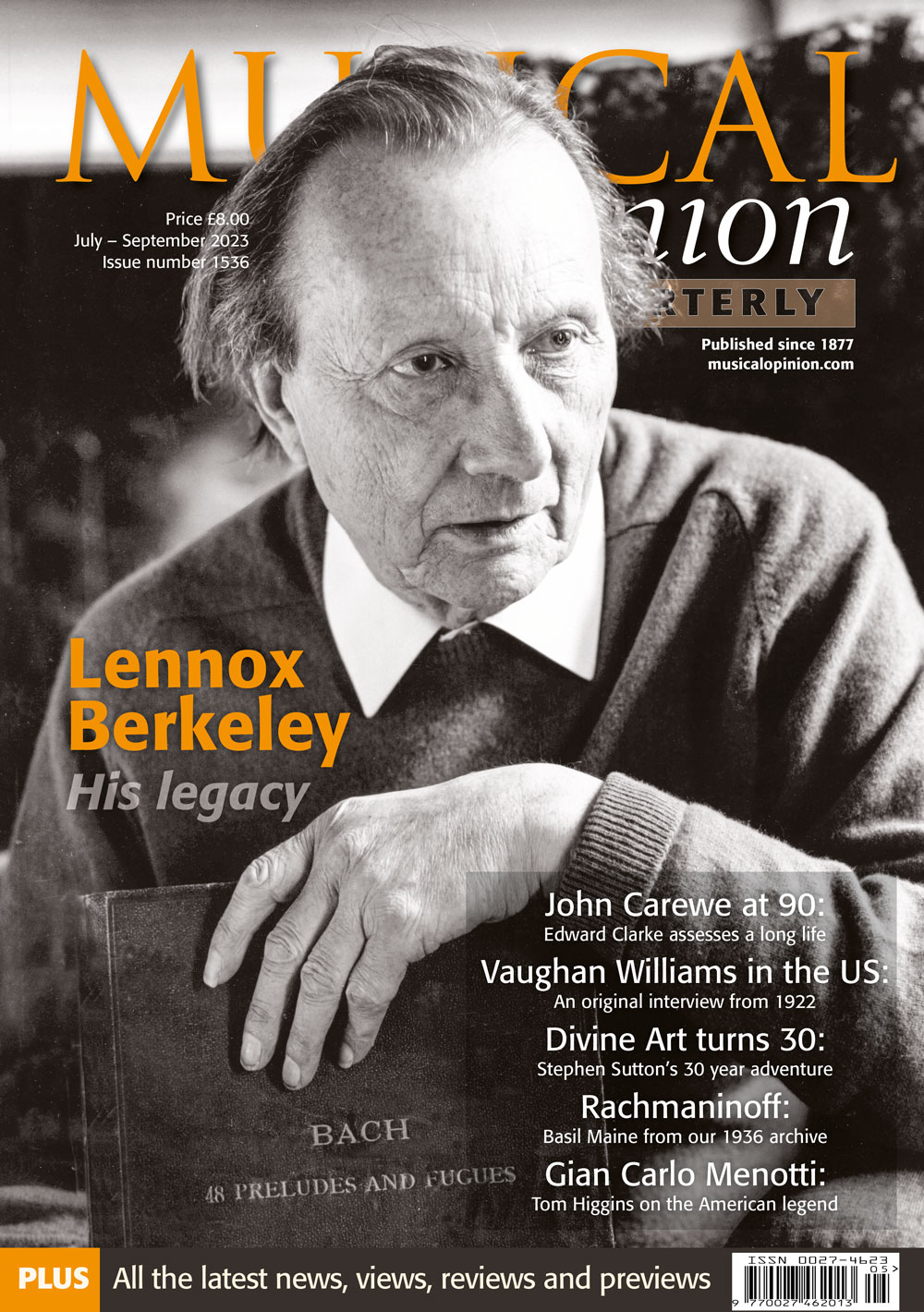

Summer 2023. 405

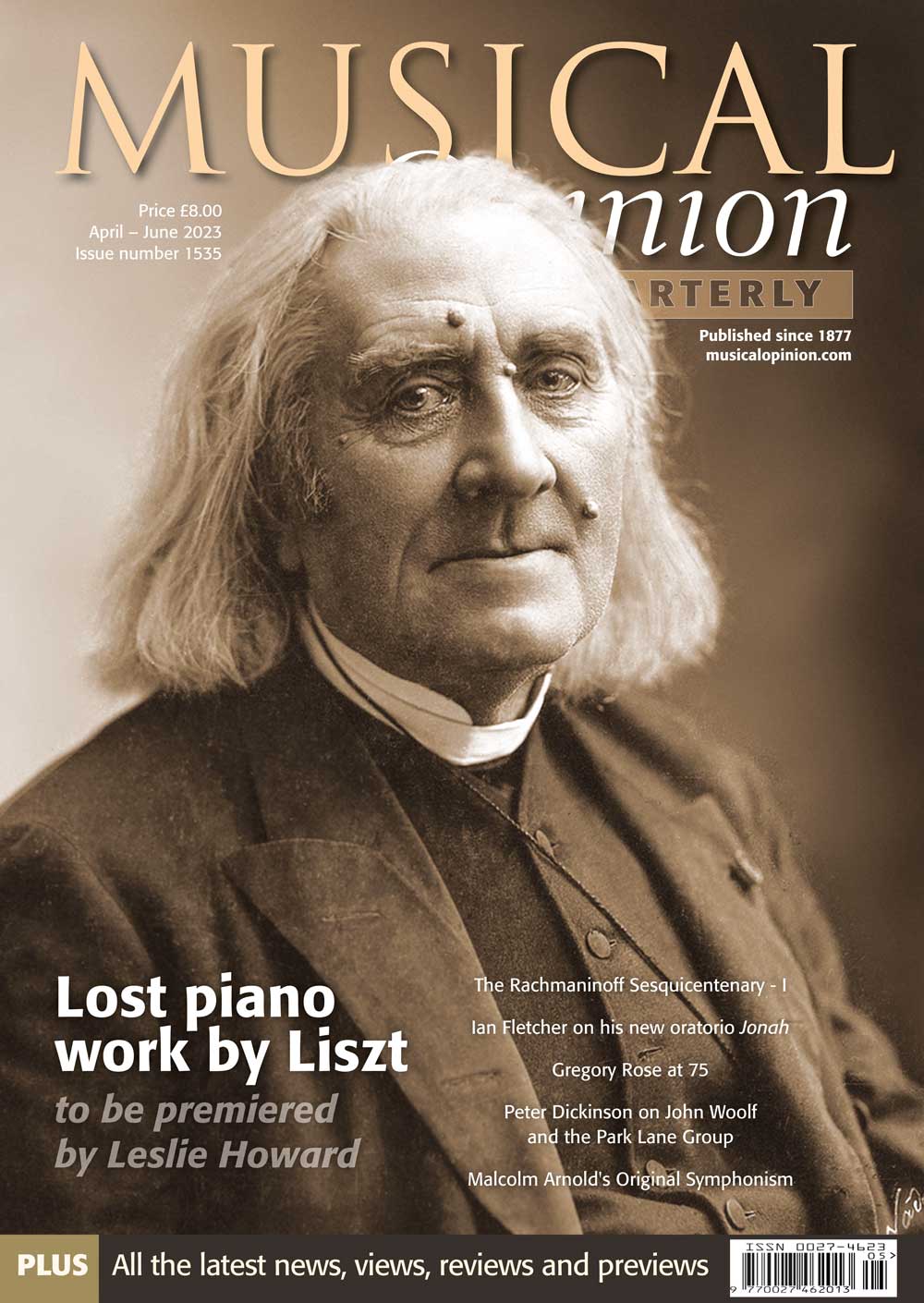

Spring 2023. 404

Winter 2023. 403

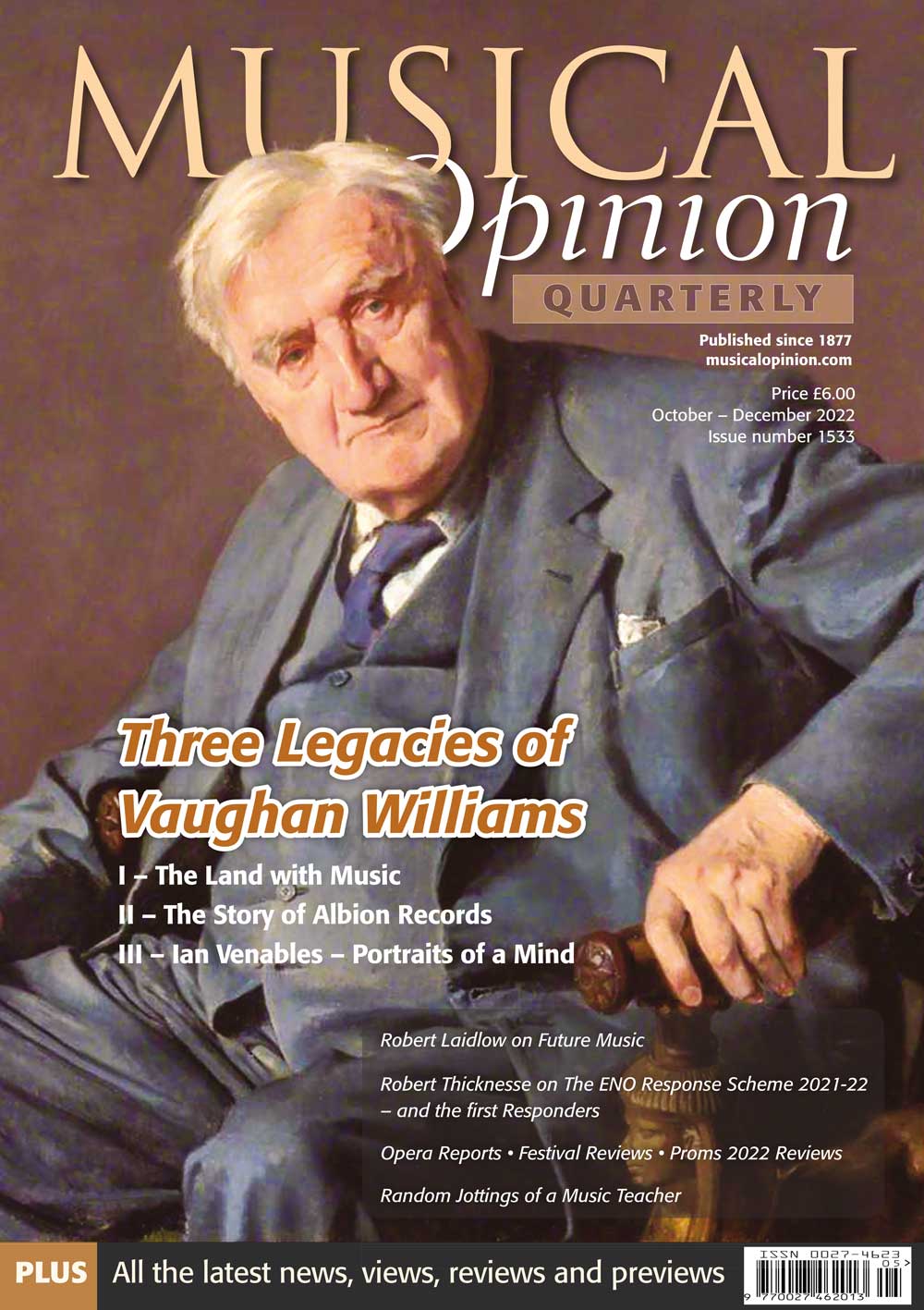

Autumn 2022. 402

Summer 2022. 401

Spring 2021. 400

Winter 2021. 399

Autumn 2021. 398

Whilst staying at A4 size and 56 pages, the magazine has been completely redesigned with different fonts (more easy to read), bigger photopgraphs, more focus on things like specifications and more CD reviews of organ repertoire.

Summer 2021. 397

Winter 2021. 395

Spring 2021. 396

Autumn 2020. 394

Summer 2020. 393

Spring 2020. 392

Winter 2019. 390

Explore By Topic

Summer 2024. 409

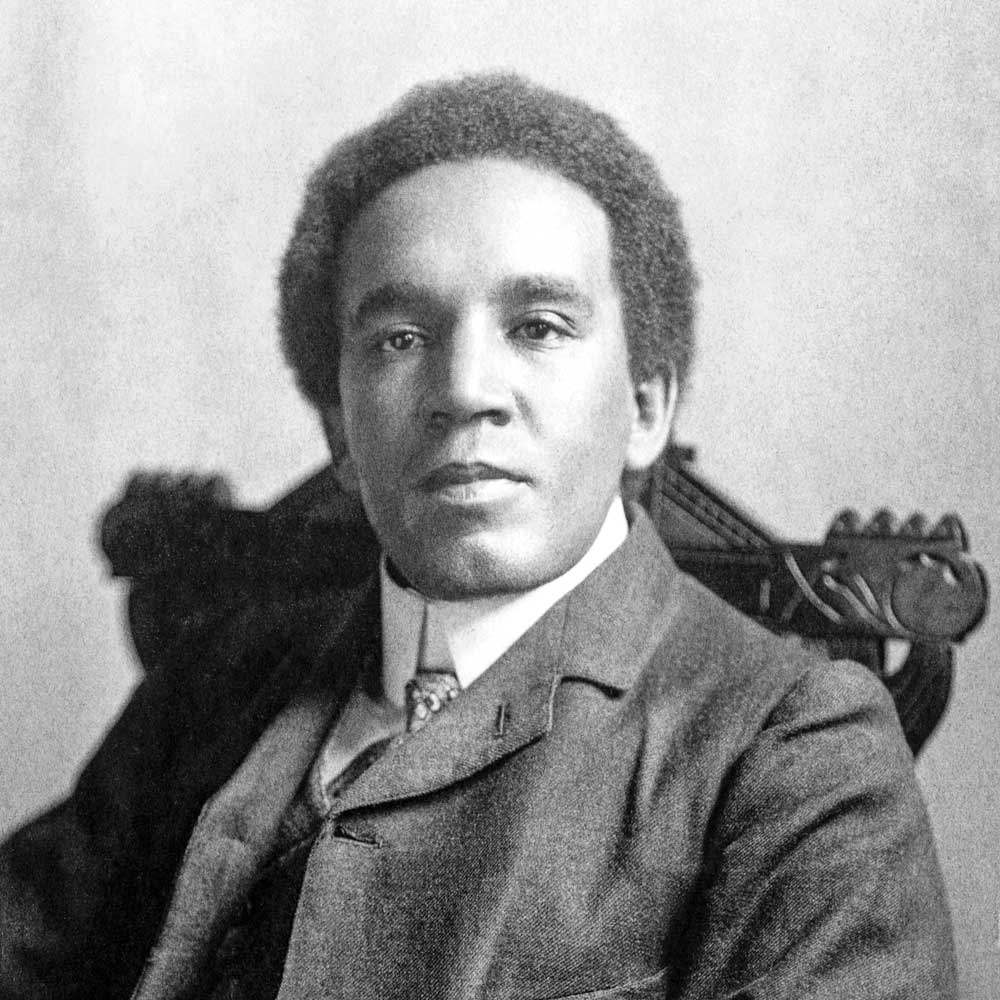

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Suite de Pièces pour Violon et Orgue, Opus 3

Dr Iain Quinn

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) was born in Holborn, London. His father was a doctor from Sierra Leone and his mother was English. Neither of his parents were especially musical although his father took an interest in the colangee, a stringed instrument associated with West Africa. His father later returned to Africa and the young Samuel grew up with his mother in Croydon. His first music teacher was his maternal grandfather, Benjamin Holman, who taught him the violin.

Coleridge-Taylor sang in the choir of St George’s Presbyterian Church, Croydon where he came under the influence of Colonel Herbert A. Walters. Walters gave him simple lessons in music theory, voice production, and solo singing, while considering himself almost a guardian to the young boy. When Walters moved to St Mary Magdalene Church, Addiscombe, Coleridge-Taylor moved with him. He was a pupil of Joseph Beckwith at the age of ten. Beckwith wrote:

I was so taken with the boy that I gave him lessons on the violin and in music generally. He was under my tuition for about seven years. During that time he was in great demand for At Homes, Soirées, &c, when he used, very prettily, to play the solos I taught him. At one of my pupils’ concerts, he was so small that I had to stand him on some boxes that he might be seen by the audience above the ferns. At that time he also had a beautiful soprano voice, and always took the solos in the anthems at, I think, St Mary’s Church, Addiscombe.

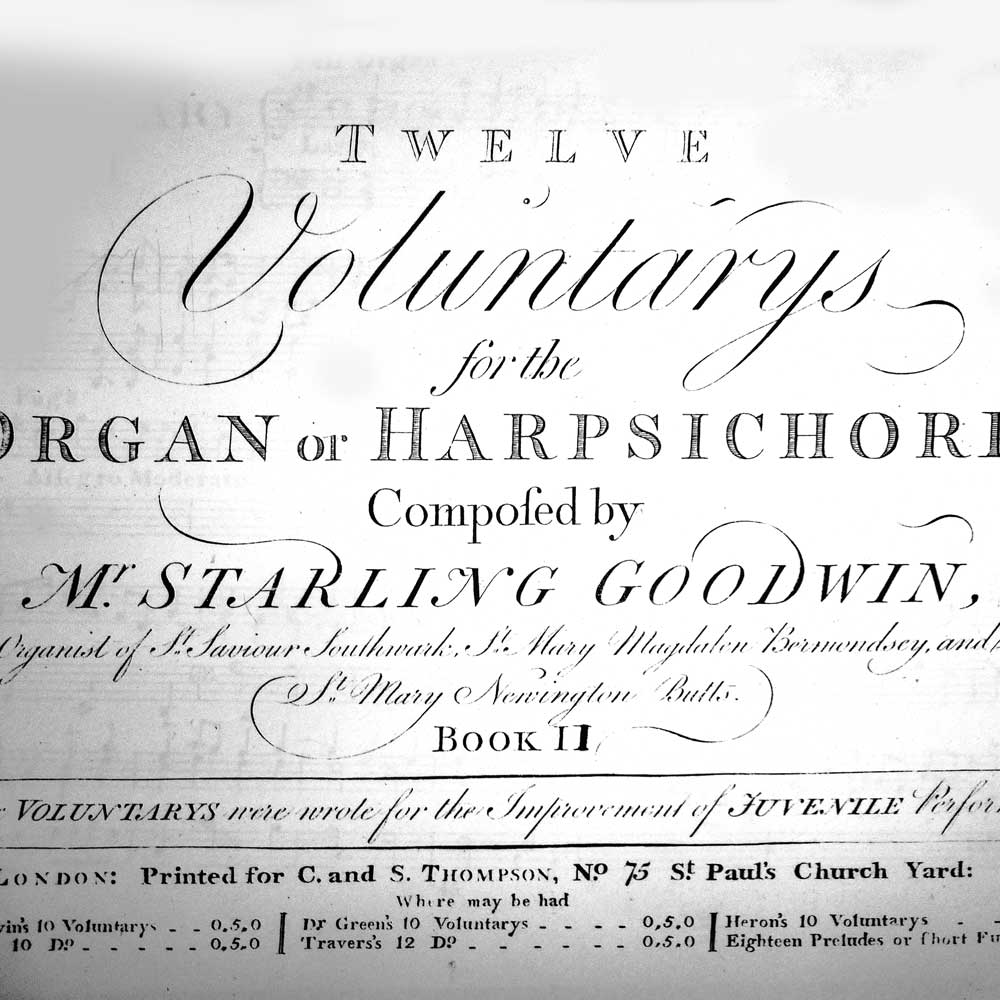

The organ music of Starling Goodwin, 1710-74. A discussion of the two volumes of 12 Voluntaries published ca. 1775 and of pieces in manuscript sources

John Collins

Starling Goodwin was organist at several London churches, according to the title page of the two sets of 12 Voluntaries by him that were published by C. and S. Thompson, after his death and which are described below in detail. Also published by C. and S. Thompson, ca. 1773, was The complete organist’s pocket book companion, containing a choice collection of psalm-tunes with their giving and interludes,; although there is no complete modern edition of this publication, several interludes were edited by C.H,Trevor in books one, three, and six of his series of Old Englsh Organ Music for Manuals. C. and S. Thompson also published A Favourite Lesson for the Harpsichord, composed by Mr. Starling Goodwin, , the music headed Sonata, and in two movements, an Allegro Moderato in C time followed by a Minuetto in 3/ 4. This is available on IMSLP. It is quite possible it would also have been played on the organ. Although the modern editions of Goodwin’s two books of Voluntaries were originally published some 17 years ago, it is timely to remind readers that 2024 is the 250th anniversary of the composer’s death in 1774. The two volumes, each containing 12 Voluntaries, were published by C and S Thompson after Goodwin’s death – maybe in 1775 and 1776, describing him as late organist of St. Saviour, Southwark (now the cathedral), St. Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey and St. Mary, Newington Butts.

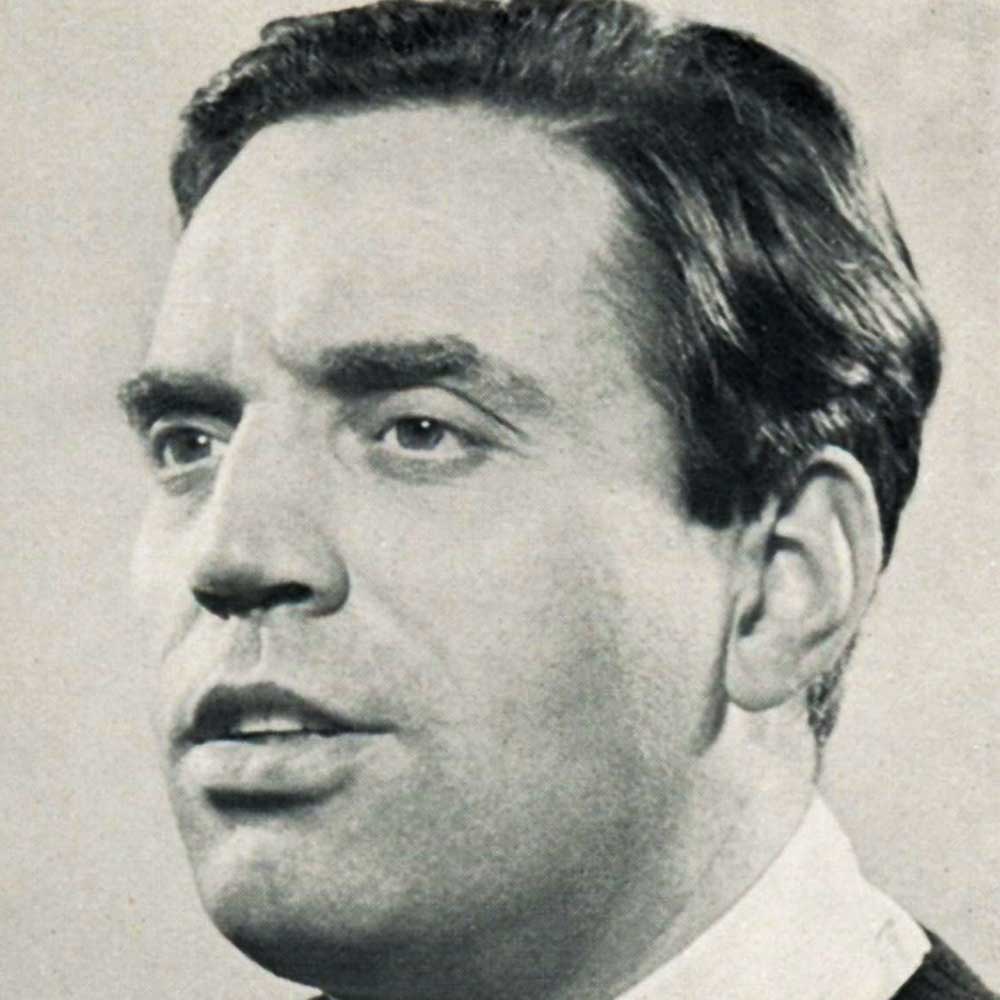

The Organ Music of John Gardner

Chris Gardner and Tom Winpenny

John Linton Gardner was born 1917 and grew up in the seaside town of Ilfracombe, in North Devon. His father, Dr Alfred Linton Gardner, was serving in the First World War as an army surgeon and was killed in his sleep in 1918 when an enemy shell landed on his farmhouse billet in France. Before the war, he had been the organist at Christ Church, Chelsea, while studying medicine, later working at Guy’s Hospital as a surgeon.

There is no doubt that John’s musicianship was encouraged and supported from an early age by his widowed mother, Muriel. She was a competent musician and, having married into a medical family, she determinedly steered John away from a career as a doctor and towards one as a musician. His early manuscripts, from the age of seven or so, survive and reveal rapid progress, with technical competence and artistic quality developing apace. Working his way through Eagle House School at Sandhurst, Berkshire, and then on to nearby Wellington College, where his place was supported by an army charity for the families of officers killed in action, he played cello in the orchestra, piano and organ, as well as composing prolifically and playing ‘rugger’ and cricket. Photo Wikimedia

Baltic Countries’ Organ Crowns

Dr Michał Szostak

Between April and July 2024, I had the opportunity to perform recitals on the largest and the most prominent organs of three East Baltic countries: the Republic of Lithuania (25,200 sq mi, 2.8 million inhabitants, Roman Catholics mostly), the Republic of Latvia (24,938 sq mi, 1.9 million inhabitants, Lutherans mostly), and the Republic of Estonia (17,504 sq mi, 1.3 million inhabitants, religionless mostly). These relatively small but closely co-operating and dynamically developing countries have many similarities (e.g., Hansa League history, communist history, regained independence in 1991, EU and NATO membership since 2004) and differences (e.g., separate languages, varied cultures, diverse dominating religions). The reach of economic and cultural legacy from the 18th and 19th centuries created a fertile background for developing the pipe organ landscape (although currently most of each society does not undertake regular religious practices). These countries’ essential instruments were built before the communist era and are currently playable thanks to extensive restoration and maintenance works.

The article describes the organ landscapes of those three East Baltic countries and the details of each country’s crucial instrument: Lithuania’s largest organ (63 stops, 3M+P) at the Church of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Apostle and Evangelist in Vilnius (i.e., Vilnius University church), Latvia’s largest organ (131 stops, 4M+P) at Holy Trinity Cathedral in Liepāja (at the same time, the world’s largest fully mechanical organ), and Estonia’s largest organ (81 stops, 3M+P) at Charles Lutheran Church in Tallinn.

With full specifications.

With many full and large specifications

St Giles, Cripplegate, London

Charles W. Pearce (1905)

This beautiful old church – which happily escaped the Great Fire of 1666 – stands at the South-west corner of Fleet Street, facing Red Cross Street. Its fine tower is an interesting feature when viewed from the Moorgate Street end of Fore Street. The final resting place of both Milton,

The Saint to whom the church is dedicated was born at Athens, and was abbot of Nismes, in France. He is the patron saint of cripples, and his Feast Day occurs in our Church Kalendar on September 1st. The foundation of the church dates back to about 1090 – its founder’s name was Alfune. Writing in 1598, John Stow says: – ‘Without the postern of Cripplegate (a place so called from cripples begging there) first is the parish church of St. Giles, a very fair and large church, lately repaired; after that the same was burnt in 1545 (the 37th of Henry VIII); by which mischance the monuments of the dead are very few: notwithstanding, I have read of these following: ‘ – [he mentions as many as forty-six, but they are all forgotten names]. Stow goes on to say, ‘there was in this church of old time a fraternity or brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, or Corpus Christi, and St. Giles, founded by John Belancer, in the reign of Edward III, the 35th year of his reign.’ The patronage of the church was originally in private hands, until it descended to one Alemund, a priest, who granted the same (after his death, and that of Hugh, his own son) to the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul’s, whereby they became not only ordinances of the Parish, but likewise Patrons of the vicarage from that time to the present.

The plan of the building consists of a nave and side aisles, with a large square tower at the west end of the nave, and a north porch. The Chancel was destroyed in the bad old times which followed the Reformatiion, and a public house was erected on its site. Until the expiration of this lease some years ago this tavern was pulled down, but the site was not restored to the church; it is still occupied by a secular building, and in consequence, the high altar stands in a mere recess at the east end of the nave, with its XVIIIth century classical wooden screen behind it. The north side of the church was (until quite recently) nearly concealed by the Quest-House, an ugly modern building in debased Gothic style, which completely covered the porch; this excrescence is now happily removed, and in its place is a pleasant grass plot, upon which a statue of Milton was erected last year (1904), at the expense of Mr John James Baddeley, Deputy of the ward of Cripplegate without. In the niche over the North porch is a beautiful figure of St. Giles in his abbot’s robes.

With full specifications. Photo: Wikimedia

St Margaret’s, Lothbury, London

Charles W. Pearce (1905)

On the north side of Lothbury, opposite to the Bank of England, is the parish church dedicated to St Margaret, a Virgin Saint of Antioch (daughter of a heathen priest), who suffered martyrdom AD 278, in the reign of the Emperor Decius, and whose Feast Day appears in the Kalendar of the English Church on July 20th. The Eastern or Greek Church celebrates her birthday under the name of Marina. The story of her triumphant witness for the Faith is picturesquely given in Dean Millman’s poem The Martyr of Antioch, portions of which were set to music by Sir Arthur Sullivan for the Leeds Festival of 1880.

The rectory is of great antiquity; we hear of John de Haslingfield, having een presented to it in 1303, by the Abbess and Convent of Barking in Essex, in whose patronage the living continued until the suppression of the religious houses in the reign of King Henry VIII, when it lapsed to the Crown, in whose gift it still continues, in alternation with the Bishop of London. The original building being greatly decayed by time, this church (like that of St Stephen, Walbrook) seems to have been rebuilt about the year 1440 on a site adjoining the same brook-side. Stow states that ‘Robert Large (Lord Mayor in 1438) gave to the choir of St Margaret’s one hundred shillings and twenty pounds for ornaments,’ and to have expended the sum of two hundred marks upon the ‘vaulting over the water-course of Walbrook running close by the said church’.

With full specifications. Photo Wikimedia