Previous Issues

Autumn 2024. 410

Summer 2024. 409

Suite de Pièces pour Violon et Orgue

Spring 2024. 408

Winter 2024. 407

Autumn 2023. 406

Summer 2023. 405

Spring 2023. 404

Winter 2023. 403

Autumn 2022. 402

Summer 2022. 401

Spring 2021. 400

Winter 2021. 399

Autumn 2021. 398

Whilst staying at A4 size and 56 pages, the magazine has been completely redesigned with different fonts (more easy to read), bigger photopgraphs, more focus on things like specifications and more CD reviews of organ repertoire.

Summer 2021. 397

Winter 2021. 395

Spring 2021. 396

Autumn 2020. 394

Summer 2020. 393

Spring 2020. 392

Explore By Topic

Winter 2019. 390

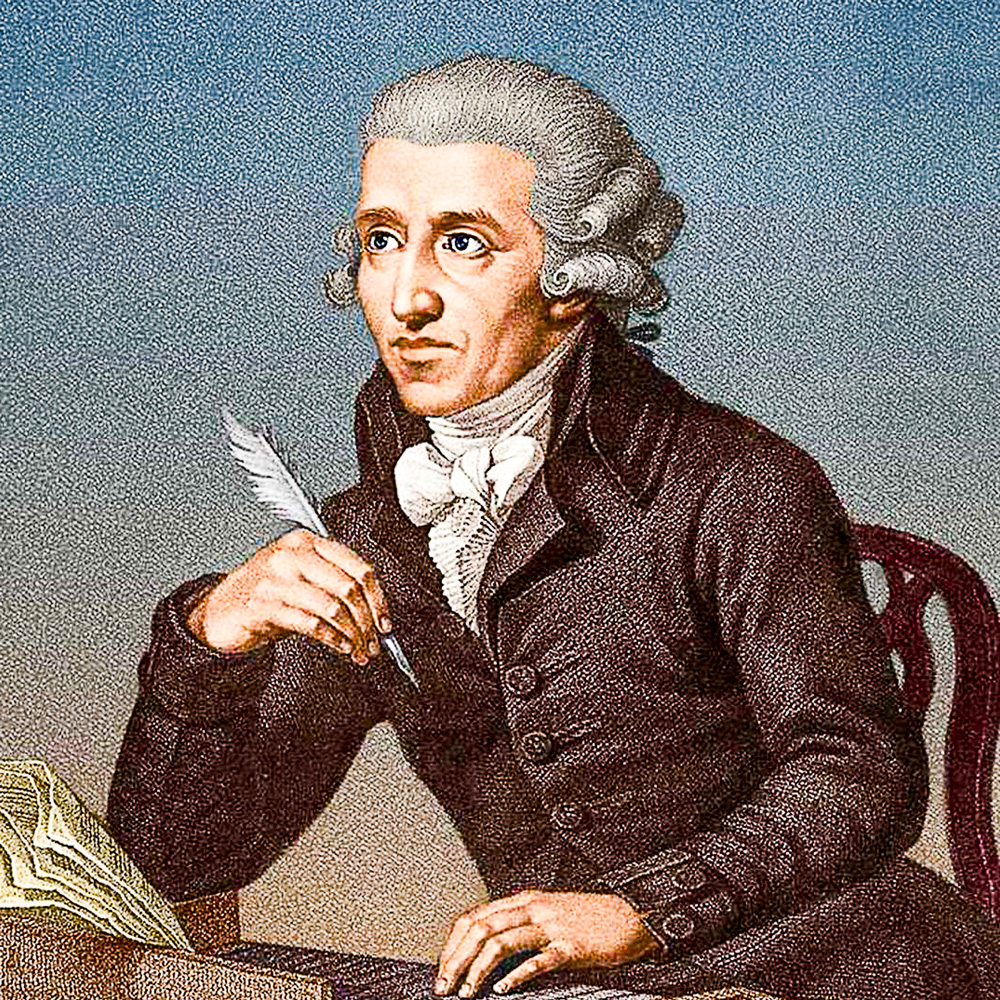

Aspects of the organ concertos of Franz Josef Haydn

Marc Vignal

Section XVIII (concertos for keyboard) of Hoboken’s catalogue consists of eleven works that are considered genuine (Hob. XVIII: 1 – 11). There are concertos for organ as well as for harpsichord or piano. In an article which appeared in 1970, Georg Feder, then director of the Joseph Haydn-Institut in Cologne, asked how many among these concertos had been intended for the organ. According to him, seven. But one of them, Hob. XVIII: 7 in F major, is nothing other than an arrangement – not realised by Haydn himself – of Trio No. 6 for harpsichord, violin, and cello (Hob. XV: 40). The two central movements are different. There remain therefore six concertos: four in C major (Hob. XVIII: 1, 5, 8, and 10), one in D major (Hob. XVIII: 2), and one in F major, a double concerto for violin and organ (Hob. XVIII: 6).

The concertos for organ are Haydn’s earliest. All seem to have been written in the 1750s, before the composer entered into the employ of the Esterházys, in 1761. It is almost impossible to establish a chronology, and almost nothing is known about the circumstances of their composition, except, at a pinch, for two of them (Hob. XVIII: 1 and 6). Authenticity of authorship is absolutely guaranteed only for these two and for a third (Hob. XVIII: 2). Some were perhaps intended for the chapel of St Anne in the summer palace of Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz (1702 – 1765), one of the most influential members of the government in Vienna: he was active in the chancellery of Bohemia.

The Hastings Recitals – Thirty-first Series 2019

Patrick Cox-Smith

In its 31st year, the All Saints, Hastings recital series continues to attract performers of the highest quality, ably illustrated by Daniel Cook on the opening night of July 8. He had travelled from his current post as Master of Music at Durham Cathedral – no mean feat when duty calls first thing on the morning following the recital! The original 25-stop Father Willis has created great interest over the years and speaks as well as ever in the generous All Saints acoustics. Lacking modern aids, it also continues to place considerable demands upon the player, especially when performing advanced repertoire with the vintage tracker action adding to the physical requirements, particularly when coupled.

The Karg-Elert arrangement of Handel’s Variations on the “Harmonious Blacksmith” with florid contrasts and full great finale set the tone for an essentially British opening half and preceded thee Opus 4 Rhapsody by Harold Darke, of St. Michael’s Cornhill fame. Not often played, the latter, with its upper register octaves and choir reed solo gave an ample illustration of the (still) superb Willis voicing. Whilst on this subject William Byrd and his Fantasia in C was an ideal vehicle for the delectable eight foot choir flute, argued by many (including the author) to be the most notable stop on the instrument. Light of tone with a hint of “chiff”, this is an outstanding tribute to the builder. The three sections of the Sonata in A minor by William Harris gave plenty of opportunity for numerous registration changes and the accurate rendition was all the more creditable when considering the paucity of stop combination aids. The post interval essential Bach, in this instance BWV 541 Prelude and Fugue in G major was given in the now “traditional” great uncoupled with pedal to great and swell for added definition to the three stop pedal division. The fugue, complete with great reed, was perhaps not to the taste of everyone, but was obviously a personal preference, and the concluding excerpts from the ever- popular Widor Vth Symphonie established the setting of the series for the Hastings audience with the obligatory Toccata finale.

One Town, One Organ, Two Churches

John Tennant

In the May-July 2000 edition of The Organ, I wrote an article detailing the history and subsequent restoration of the instrument in the church of St John, Egremont, Wallasey, a town on the Wirral Peninsular, then in Cheshire, now in Merseyside. To sum up, an 1833 instrument built locally by Bewsher & Fleetwood, but repaired and enlarged by Hele in 1902, underwent a full restoration in 1999 by Harrison & Harrison, thanks in part to grants from The Foundation for Sport and the Arts and from the then called “Heritage Lottery Fund.” Sadly and as happens all too often, disputes between clergy, organists and choristers, saw a rapid decrease in the congregation and the departure of most musicians. Unsurprisingly, the church underwent a rapid decline holding its last service in 2002 being declared redundant in 2005.

Meanwhile, a couple of miles up the road, but still in Wallasey, moves were afoot in another church, to initiate a comprehensive rebuild of their organ, also built by Hele. This was the 1865 George Gilbert Scott church of St James, in the seaside district of New Brighton and it is this that we are currently discussing.

In the closing years of the 19C., their vicar was Charles Henry Hylton Stewart, (not to be confused with his famous son, the organist and composer, also Charles Hylton Stewart.)

The Organ Manual

Anna Hallett

You may question whether there is a need for another organ related website. You may well be thinking that there is nothing new that another site cannot offer. You may indeed consider the market to be saturated. Please allow me to provide you with a new perspective.

The Organ Manual came about as a result of extensive research for a project I undertook called ‘Inspiring Young Organists – does more need to be done?’ about which I wrote in these pages in the Spring 2019 issue. In the process of my research I received responses from over 250 organists of all ages, levels of playing and background. I had responses from 9-year olds through to 90-year olds. I had responses from the reluctant organist, the eager student, and the recitalist. No matter their age or level of playing there were core similarities, such as the exams that they had taken, where they had practised or qualifications held. There were also some notable differences, for example the memberships that they held, how lessons were/had been financed and their subscriptions to organisations. In order to keep track of all the information that I received, as well as collating it in tables, charts and statistics, I also started creating lists of similar categories of information. Page after page of them!

The art of stylish organ improvisation

Dr Michal Szostak

The spontaneous musical activity of a man was the main source from which the entire musical culture of humanity was born. Before musicians started composing repetitive works, improvised music was used both for entertainment and for the needs of worship. For centuries, along with the development of instruments, the development of playing techniques has continued. The adaptation of the organ for the use of the Western Church implied a dynamic development of this wonderful instrument. The flexibility of the liturgy meant that improvisation was the most optimal way of implementing live music during worship. In principle, until the early second half of the 19th century, improvisation was the dominant form of organ playing. At that time, where organs in concert halls were located (e.g. Albert Hall in Sheffield, The Royal Albert’s Hall in London, Palais Trocadéro in Paris), and with the regular giving of concerts in such venues, printed organ literature began to appear more regularly.

The subject of this article is the issue of showing the methodology of the performer’s approach to the art of stylish organ improvisation, which, after a period of stagnation at the turn of the 19th and 20th century, has been experiencing its renaissance in recent decades. Detailed analyses will be provided on the base of the 19th-century French symphonic era, but the same approach and methodology can be used for each epoch and each style.