Previous Issues

Autumn 2024. 410

Summer 2024. 409

Suite de Pièces pour Violon et Orgue

Spring 2024. 408

Autumn 2023. 406

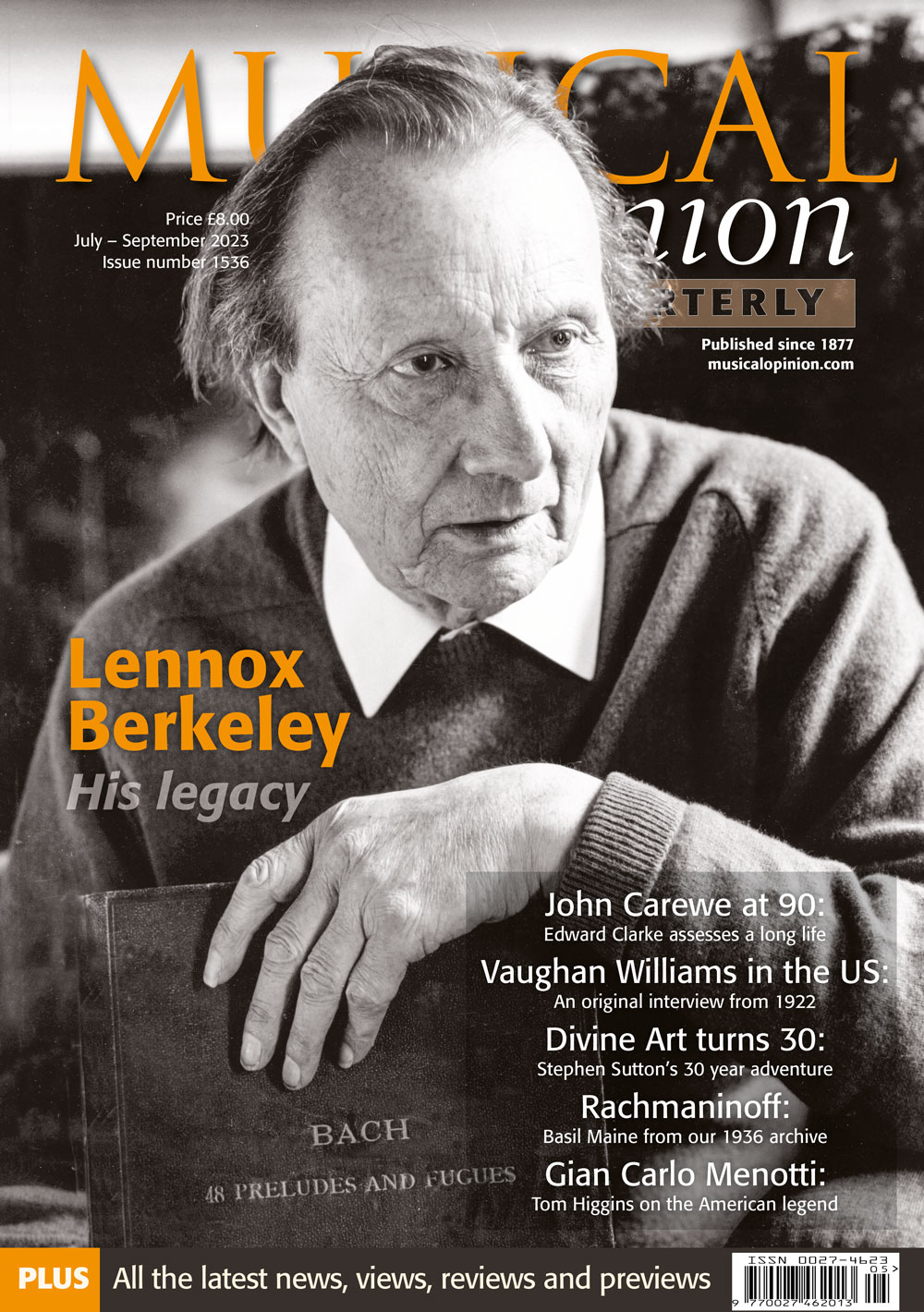

Summer 2023. 405

Spring 2023. 404

Winter 2023. 403

Autumn 2022. 402

Summer 2022. 401

Spring 2021. 400

Winter 2021. 399

Autumn 2021. 398

Whilst staying at A4 size and 56 pages, the magazine has been completely redesigned with different fonts (more easy to read), bigger photopgraphs, more focus on things like specifications and more CD reviews of organ repertoire.

Summer 2021. 397

Winter 2021. 395

Spring 2021. 396

Autumn 2020. 394

Summer 2020. 393

Spring 2020. 392

Winter 2019. 390

Explore By Topic

Winter 2024. 407

The Organ Sonatas of William Faulkes and Frederick Bridge

Dr Iain Quinn

The latest In Dr Quinn’s survey of the repertoire of British Organ Sonatas

The organ sonatas of William Faulkes (1863-1933) and J. Frederick Bridge (1844-1924) are elegant examples of the style that many Victorian composers fostered in their writing for the developing symphonic organ in England. They are playable on both small and large instruments and allow for creativity in registration. They are also of limited technical difficulty and have an inimitable charm that could relate well to an audience and congregation alike. As discussed in The Genesis and Development of an English Organ Sonata (2017), the English sonatas had an important pedagogical role jointly inherited from Mendelssohn’s very practical and popular approach to the instrument and the continued European legacy of the lesson-sonata tradition whereby in learning a piece you also learned the instrument and vice versa.

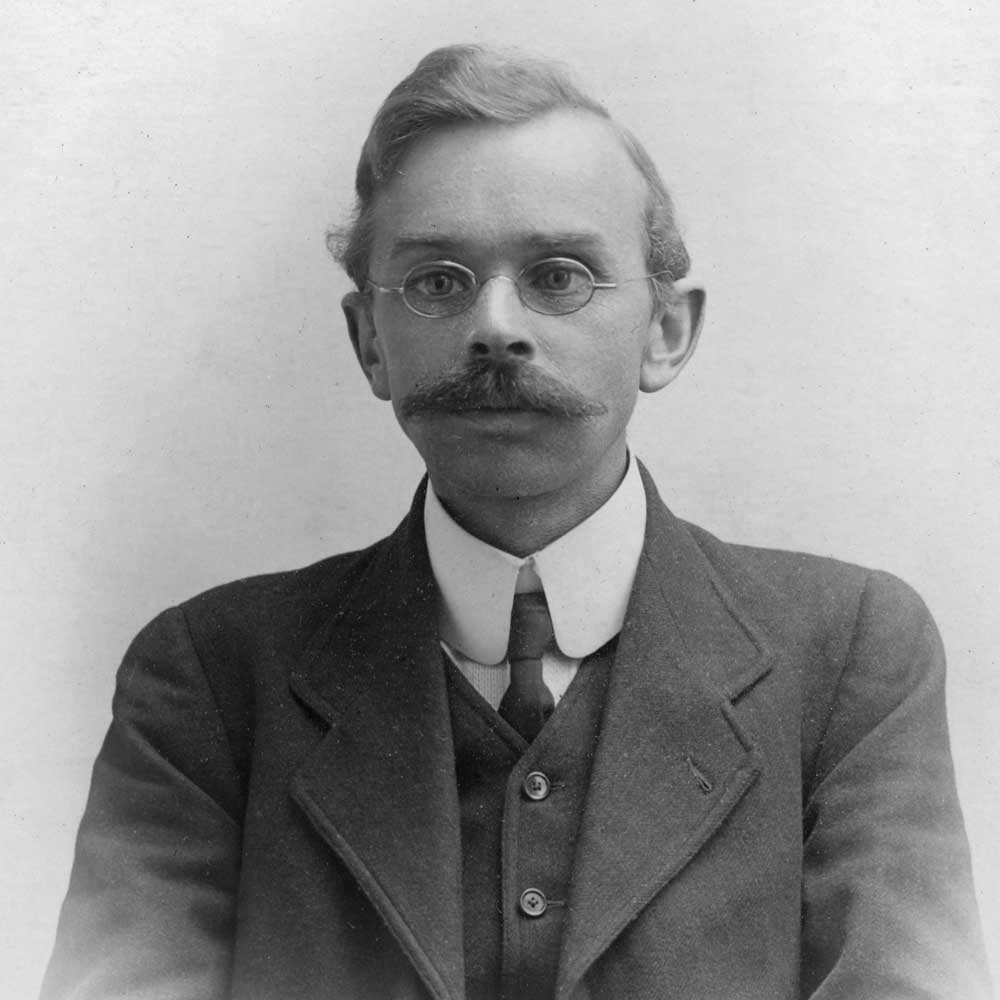

William Faulkes (1863-1933)

In 1919 an article appeared in The American Organist magazine that began with a summation of the popular appeal of Faulkes: when the embryonic organist is just learning to walk across the yawning chasms of the pedal board he meets among his first friends one who is to remain his friend for life – William Faulkes. Amid all the dry and uninteresting hours that must be devoted to purely technical matters how refreshing it is to both teacher and pupil to rest for a moment upon one of the truly organistic compositions of William Faulkes; and when years of effort have been crowned by a smooth technical proficiency and the student has not yet lost his love of pure musical beauties how delightful it is to open a recital with [the] Concert Overture in E flat by William Faulkes; between the two periods lies a wealth of practical organ music that is hardly excelled by any one composer.

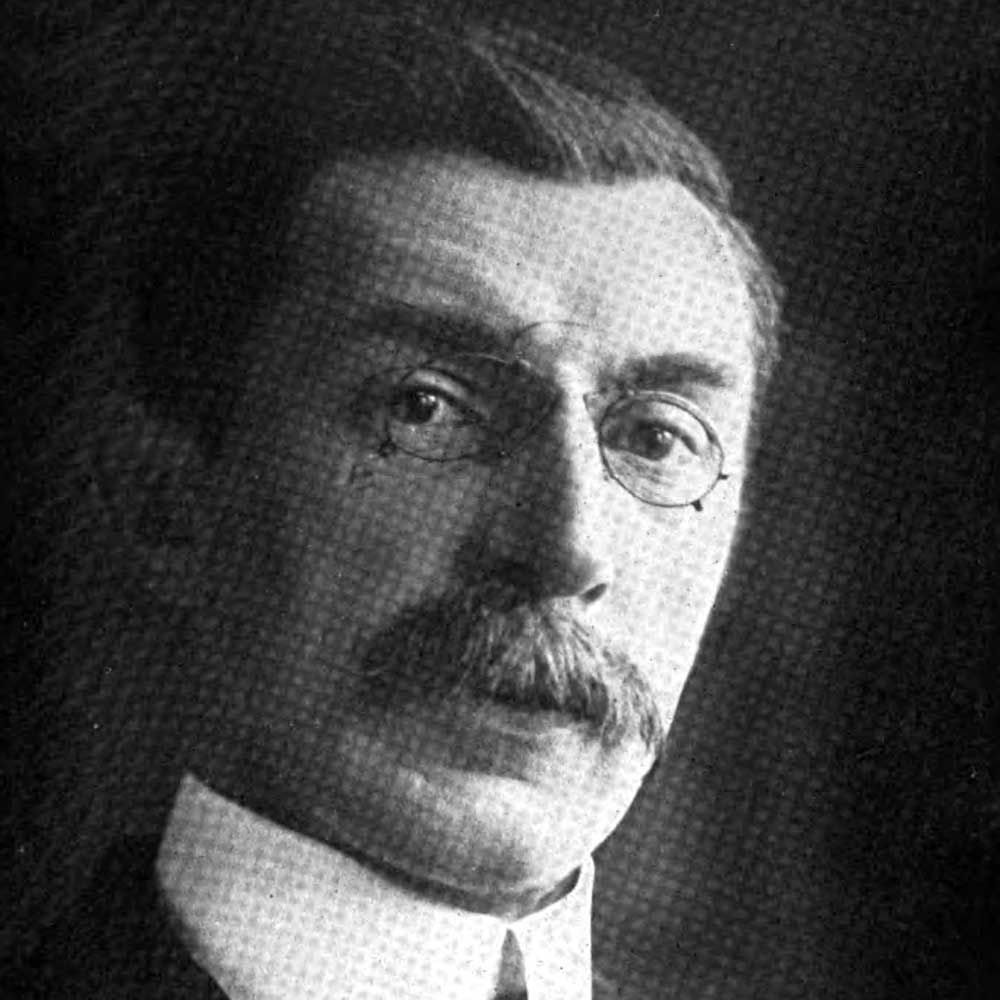

Henry Hackett FRCO, organist and composer

by Nigel Hackett

It is fitting that this article appears in this illustrious journal, given that Henry Hackett was a ‘regular contributor’ to The Organ. His voice in these articles is clear: ‘How rarely … one finds any organ furnished with a piston to control this combination [‘full swell used minus the flue work’] for a forte passage in the swell is far clearer and more effective as such.’ In another article, on ‘The Birmingham University Organ’, he commended the beauty of the University’s Great Hall, saying ‘An organ is really but half of an instrument one might say, the other half being the building in which it is erected’, before describing ‘The magnificent roll of the glorious diapasons still remain a thrill in the writer’s memory’. In the same article, I am struck by the modernity of his language in describing technically the organ ‘in spite of the four rank mixture and an incisive fifteenth [the full great] is far from being screamy.’

As set out in our introductory article [The Organ No 405 August – October 2023], Henry Hackett was born in Smethwick, Staffordshire on 12 November 1872, the son of John Hackett (1843-1925), a machinist, and Mary Jane Hannah Camm (1847-1938), whose brother Thomas Willliam Camm (1839-1912) was a leading stained glass artist and founder of the Camm family firm. His sons Walter & Robert and particularly his daughter Florence (1874-1960) went on to gain ‘international acclaim’ for their work as stained glass artists.

How Henry’s aptitude for music was discovered, we do not know, but there must have been a strong church connection in the family. We can only surmise that the family worshipped at St. Augustine’s, Edgbaston, given that Henry Hackett became a ‘pupil of Dr. A. Gaul, of Birmingham’ who was the organist at St. Augustine’s.

St. Bride’s, Fleet Street

Charles W. Pearce (1905)

A brief sketch of the history of this church previous to the Great Fire of 1666 is thus given in the original edition (1603) of Stow’s Survey of London:

“The parish church of St Bridges, or Bride, of old time a small thing, which now remaineth to be the choir, but since increased with a large body and side aisles to the west, at the charges of William Venor, Esquire, Warden of the Fleet, about the year 1480. The partition betwixt the old work and the new (sometime prepared as a screen to be set up in the Hall of the Duke of Somerset’s house at Strand) was bought for £160, and set up in the year 1557; one wilful body began to spoil and break the same in the year 1596, but was by the high commissioners forced to make it up again, and so it resteth. John Ulsthorpe, William Evesham , John Wigan, and others, founded chantries there.”

The abbot and convent of Westminster were patrons of the living, which in medieval times was a rectory. There was also a vicarage founded and endowed about the year 1529, and King Henry VIII, after the dissolution of the convent at Westminster, having given the rectory and parish church of St Bride to the new collegiate foundation of Westminster established by him, St Bride’s has continued a vicarage in the gift of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster. In 1610, the Earl of Dorset gave a piece of ground, on the west side of Fleet ditch, for a new churchyard; this was consecrated on August 2nd, 1610, by the Bishop of London (Dr George Abbott).

Organ landscapes in Kazakhstan

Dr Michal Szostak

In August 2023, at the invitation of the Catholic bishop of Karaganda, Msgr. Adelio Dell’Oro, I visited Kazakhstan in central Asia to perform three recitals in the Karaganda region. Kazakhstan is not a place where organs are popular; I would rather even say that the majority of Kazakh society barely associates the word “organ” with a musical instrument. However, all venues (Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Fatima in Karaganda, Birth of Our Lady Church in Szachtinsk, and the church of Our Lady Mother of the Church in Karaganda- Fedorovka) were fully taken during all recitals, and the reception of organ music was enthusiastically warm.

This article aims 1. to analyse the socio-cultural background of organ music in Kazakhstan, 2. to introduce very limited number of pipe organs located in this geographically enormous country, and 3. to shortly describe the history of organ-building companies (Alexander Schuke Orgelbau from Potsdam in Germany, Rieger-Kloss from Krnov in Czechoslovakia that bankrupted in 2018, Hugo Meyer Orgelbau from Heusweiler in Germany, and Pflüger Orgelbau from Feldkirch in Austrian, that finished its existence in 2015).

Organ Improvisation - connecting, welcoming, conceiving, acting

Jean-Pierre Leguay

Against the background of this year’s Haarlem Organ Improvisation Competition, the distinguished organist and author offers his insight into this intriguing subject. Translated from the French (July 2023) by Robert Matthew-Walker

“Improvisation is a user’s art,” said the composer Claude Ballif, thus emphasising the important role within the current practice of instantaneous reactivity, of perception within the present moment, the consideration of a given situation and its guiding journey towards the future. Just as walking is learned by walking, the mastery of techniques by the craftsman increases and becomes more refined, gaining in skill and proliferating perspective by the combined actions of growing experience and diversity in application, together with fresh approaches in the ability to improvise.

Such reactions to musical events are acquired in the same way, with the constant engagement of the ear, the memory and the physical body. There can be no true initiation without anticipation, without calling, without the patience of a slow growth, and thereby gradually revealing the truth for those who wish to acquire these aspects of musical performance.

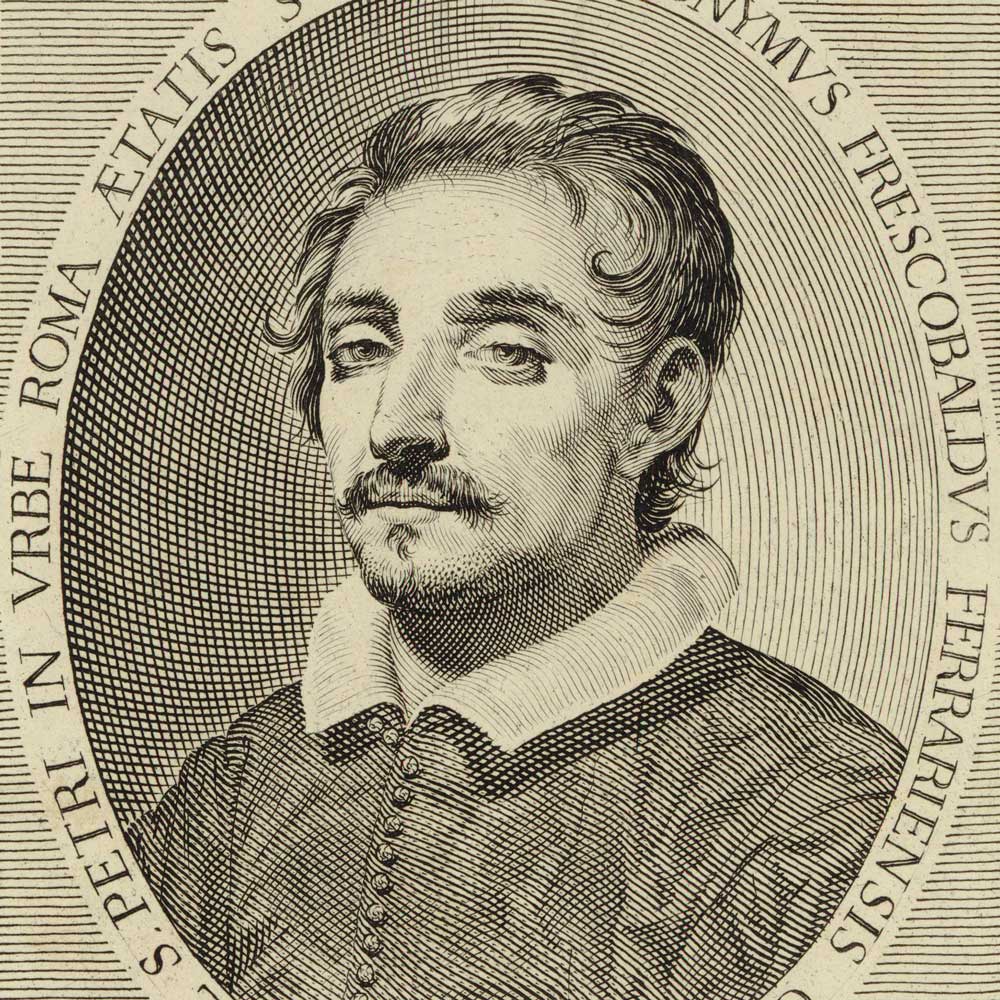

Girolamo Frescobaldi: Organ and keyboard works II Capricci.

John Collins

The 1620s saw a remarkable series of publications across Europe presenting the repertoire of an individual composer – Manuel Rodrigues Coelho in 1620, Francisco Correa de Arauxo, in 1626 Samuel Scheidt in 1624, Girolamo Frescobaldi and Steigleder both in 1624 and 1627 and Jacques Titelouze in 1623 and 1626. This year, 2024, sees the 400thanniversary of the publication of three important collections of music for keyboard instruments, namely Il primo libro di Capricci by Girolamo Frescobaldi, the Ricercars by Johann Ulrich Steigleder and the massive Tablatura Nova, originally issued in three parts, by Samuel Scheidt In this article/review I shall look at the prints by Frescobaldi and Steigleder and discuss their importance, not just for their time but also for us today.

Girolamo Frescobaldi, 1583-1643, was organist at St. Peter’s Rome, and published seven collections of pieces for keyboard, embracing all genres, as well as chamber and vocal music. His earliest publicatio, Twelve Fantasias, of 1606 is a set of quite academic contrapuntal pieces, published, as with the succeeding volumes of polyphonic pieces, in open score. This volume was never reprinted.

Crossing borders

Andrew Jolliffe describes the new Mascioni organ in the Church of the Santissimo Crocifisso at Ponte Tresa, Italy.

Perched neatly on the shores of Lake Lugano, the border town of Ponte Tresa is where two worlds collide. One exudes laid-back Italian charm, the other brisk, no-nonsense Swiss efficiency. That said, they complement one another. Where nations fuse, their languages, homes, tastes and even mannerisms mix in weird and extraordinary ways.

Even in the middle ages, the town’s location made it a crucial trading-post between the two countries. Wine, shoes, currencies and more besides have changed hands here over time. The batteries of extravagant villas on the slopes above testify that the folk of Ponte Tresa lived well, with tourists from all over Europe joining them to revel in the heart-stopping lakeside views.

Hence the town grew, so in the late 1950s the architect Luigi Crespi was commissioned to conceive its second church. The result was like nothing seen before or after it. Built entirely in reinforced concrete, the Chiesa del Santissimo Crocifisso is scallop-shaped, complete with an undulating roof radiating from a point behind the west end. The interior is adorned with artworks from Muttenz in Switzerland’s German quarter, and an intriguing ceramic crucifix by local artist Antonio Galati. But while Crespi was clearly a creative architect, he was no acoustician. With such an abundance of waves, grand sweeps and conflicting curves, the sound quality sits somewhere between a swimming pool and an abattoir with a stony 5-second reverberation. Here, a simple clap of the hands becomes a box in the ears.